Roshi Joan Halifax, Ph.D. is a Buddhist teacher, Founder and Head Teacher of Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, a social activist, author, and in her early years was an anthropologist at Columbia University (1964-68) and University of Miami School of Medicine (1970-72). She is a pioneer in the field of end-of-life care. She has lectured on the subject of death and dying at many academic institutions and medical centers around the world.

November 18, 2022

After a short introduction of all the members attending the meeting, Roshi explained her two and a half year retreat in the mountains having now turned 80 years old. She then engaged in a 90 minute question and answer session with the group.

Q: There is a deepening narrative about society coming into crises in Sweden. This includes many areas: economic, political, societal and ultimately personal, which has had clear effects on chaplaincy. I read your article on wise hope and I found it very interesting. Could you share something on how to carry wise hope in our chaplaincy in this situation where negativity is mounting and hope is being lost?

Roshi: This is a very important question. In Buddhism both hope and fear are considered “nemesis”. When I was told to give a talk on hope at Soji-ji Temple, one of the centers of Soto Zen Buddhism in Japan, I “face palmed”, although I ended up doing it since I tend towards obedience and curiosity. It seems that more people are trying to understand hope right now, since there is a sense of futility, a general perception of a catastrophic future and present. The question is, how do we work with hope in a way that is generative?

When working in the field of chaplaincy, medicine, social justice, environmental issues or any kind of service to others, the beginning is important, we have to recognize that we are doing “charnel ground practice”. This notion of charnel ground practice has been with me for a long time, but highlighted by Roshi Bernie Glassman. He had the guts to start the bearing witness retreats at which I was present for several. During one of these at at Auschwitz, I was taken apart but put back together in a new way, through deep consideration of the horrors of war and cruelty without being fundamentally traumatized.

We move towards suffering without falling into it ourselves. The encounter with the grotesque decay of society, the sense of decomposition of the world is the place for our awakening. It is important to recognize that this kind of practice is about being in a landscape of fundamental liminality, between two worlds encountering each other, life and death.

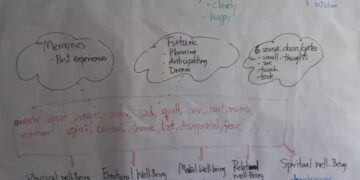

Exercise: Imagine coming alongside someone completely without hope, completely futile, perhaps a young person you know, someone who wants to take their own life. What comes up for you? What experience in the body? What did you feel?

Respondent #1: I have stayed silent and I do not understand why. I have the feeling that it could be me but it is not me. For some reason, I remember being about 20 years old reading about your work at a train station in Sweden and I felt inspired by this to do chaplaincy work. Especially due to the Noble Eightfold Path, I got a feeling that there is something to be done, that there is really a path to follow, even though there is no solution.

Respondent #2: I had a visualization of a wide river, of a person in need of help, and of a reaching hand. My feeling was of a need to help that person, having a sensation that if not, he/she would drown. I also felt that the outcome of helping was uncertain, and that I myself could fall in the river as well.

Respondent #3: I have had many experiences of being with dying patients, fortunately most of them have passed peacefully. I imagined those that have struggled with stage 4 diagnosis of cancer, situations in which I felt powerless, unable to offer anything. I realized then that the issue can jump to another person, so I wished, through the practice of tonglen, that their heart and mind be calmed.

Respondent #4: I felt hope and a shining light, a push to just stay with the person in front of me and to share as much time as possible as we walk home together.

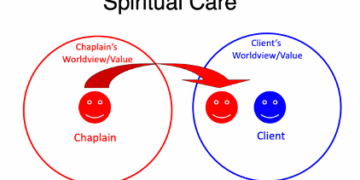

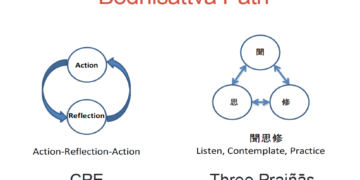

Roshi Joan: Indeed everything from suffering is contagious. How do we maintain a mindset that is joyful but not icky amidst despair conditions? From the Mahayana perspective, there is an algorithm related to the bodhisattva and the vows, which are endless. It’s important to remember Dogen emphasis on “continuous practice”, as well as Okumura Roshi’s talk that I listened to recently that, “You never graduate”. You are constantly tacking and going off course, by falling over the edge you are more alive. Bringing your attention to the moment so clearly aids you in recognizing that you are at the effect of winds of change, otherwise you can never get to the pure land or enlightenment. The key is continuous practice. “Just keep showing up and doing it”. Your relationships are very important since in chaplaincy it is very important that you connect. But there is also a Lone Ranger-ness to chaplaincy.

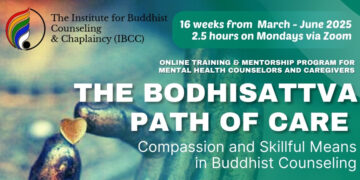

An antidote is a strong practice. We need to be aware of where we choose to work so that our mindset is good as a result. How can you stay healthy in the midst of your service in the “charnel grounds”? The bodhisattva’s perspective is that the aspiration to end suffering is not just for your mother or your dog or the hospital you are working at. Ultimately, the assignment is not small; it is for all beings. The first of the four bodhisattva vows is, “Creations (sentient beings) are numberless I vow to free them all”. There is an endlessness to our vows and practice. It is essential to keep showing up in the midst of complex conditions, just like Okano-san, Fujio-san, and Jon.

Q: How does hope relate to your desire to end suffering?

Roshi Joan: We can say we are a bodhisattva and still feel futile. We need to make actions in order to work on the previously mentioned assignment. I want to add a quote by Suzuki Roshi who said, “Life is like stepping onto a boat that is about to set out to sea and sink”.

Conventional hope can be a nemesis and partner up with fear. There is always some kind of ghost or spirit of dread that is hanging out. When you want the person you are caring for to “die well”, this is a dimension of hope. There is another kind of hope, which is wise and not attached to outcome. This wise hope is born out of the experience of radical uncertainty. For example, Bernie Glassman talked about “not knowing”, which is being in the trusting emergence, even if negative factors emerge. Wise hope is close to Joanna Macy’s “active hope”, “active” being the engagement and “wise” the ground. These are valences of each other, wisdom feeds active hope. If we choose to do “charnel ground work” that choice is hopefully from a deep place of service, not from the “bodhisattva button”, which would be materialistic to a degree. No matter what, the truth of impermanence will prevail.

There is a whole set of people that love to do stuff that is dangerous and edgy out of a need of the self; they get off on it. That is important to reflect on – why? Are you seeking social recognition and praise. Or to get high on this experience? Or have you dropped down into a deeper level related to the bodhisattva imperative? Or having some taste of nonduality, have you experienced emptiness?

Wise hope reflects the realization that what we do matters. Throwing trash out of the car window matters, but we might not know how it matters, where, what, or whom it may impact. However, there is a fundamental understanding that arises in the context of our own spiritual formation, our relationship with a community of reflection, in which we understand the nature of consequentiality. Then we find that it does matter what we consume or choose not to consume. This is not only about feeding but also about ending suffering. Wise hope understands that minding what we do really matters. The vow that we take is endless. How do we show up in the midst of the great complexity we are facing today?

I am always working with the question of the 84,000 dharma doors. I am kind of freaked out by the people from the extinction – rebellion movement who threw soup on the Van Gogh painting. I don’t think I could do the extinction rebellion thing. There will be many ways that our sense of justice is going to be addressed in terms of social or environmental engagement, and some of those doors are not ones that I would want to be passing through. As I think about chaplaincy, in a certain way, the actions of the chaplain are the manifestation of the Lotus Sutra mantra, meaning that through the whole system of chaplaincy we can become the embodiment of the bodhisattva vows and “wise hope”. You don’t know the downstream effects, but you know this is the right thing to do. Not doing it erodes one’s sense of character.

These words come to mind by Rachel Naomi Raymen about how helping, fixing, and serving are three ways of looking at life. She said,”When you help, you are seeing the person as weak; when you fix, you are seeing the person as broken; when you serve, you are seeing the person as whole”.

I also think about Shantideva’s A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. In this teaching, if you step on a thorn, your hand goes immediately to the foot to pull out the thorn. Like this, how do we create the conditions of wholeness and non separateness? I just got back from India where I moderated a science panel in the living room of the Dalai Lama with some amazing scientists. Then there was a meeting with compassionate young leaders. The Dalai Lama shared with these young leaders from around the world, people from every dimension of service. He kept saying that there is only one antidote and that is the cultivation of an altruistic heart. His words were inspiring in relation to his many years in exile. How did he manage to transform the tragic circumstances of his life? The same for Thich Nhat Hanh, Malala Yousafzai, and Nelson Mandela – their way out of hopelessness and out of despair was on the path of caring for others. This is why I love chaplaincy and the social and environmental engagement being done around the world.

Q: I wanted to take the opportunity to ask about joy, how do we maintain this?

Roshi Joan: The Dalai Lama and Archbishop Tutu, who are wonderful role models, have this buoyancy in the midst. In The Book of Joy that they co-authored, we can understand that if we walk heavy with gloom and doom, it is a virus we are carrying. We could be carrying the virus of joy instead. Toxic positivity is not joy. Real joy comes from some level of awakening. In Japanese, there is the term “grandmother’s heart” (roba-shin 老婆心). Desmond Tutu had this. Another concept is is the Pali/Sanskri Buddhist term viriya, which I translate as wholeheartedness and not so much as exertion or effort. “Grandmother’s heart” is essential and joy is important but not fake it till you make it.