Ouyporn Khuankaew is a Buddhist feminist activist and has been a workshop facilitator in Asia since 1995. She facilitates workshops on feminist counseling, sexuality and anti-oppression, peacebuilding, and nonviolent direct action with Thai NGO and government workers, with regional and international participants. She also guides meditation retreats for activists. Prior to the International Women’s Partnership for Peace and Justice (IWP), she ran the gender program of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists. Ouyporn is now working with trauma and ADHD and exploring how Buddhism and its philosophies can fit into this paradigm. Buddhist philosophy has helped her with work, people and in her personal life, and as a result she would like to deepen the practice elements as well.

January 20, 2023

Introduction:

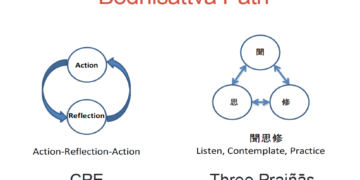

I miss sharing with peers who are doing this work, so it is a pleasure to be here today. I have been working with different trauma survivors starting with myself, my mother, and my siblings. I have also worked with refugees in Indochina right after university, then moved on to the north of Thailand to work with tribal people. In 1996 I worked at the Wongsanit Ashram with different groups from Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. I didn’t realize 70% of the people I worked with were trauma survivors, something which set me on my path. I also teach psychologists, NGO workers and other people in supporting roles to understand and eventually teach structural oppression.

Discrimination and Empathy

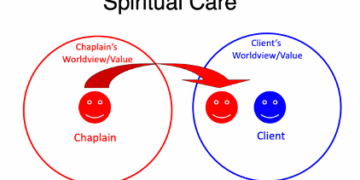

Trauma is complex and working with it takes a long time. There are unfortunately many marginalized identities and vast forms of structural discrimination. Without this understanding, the “healers” point only to individual problems and behavioral change. I work to transform the internalization of privileged people to understand structural oppression. Once they understand and integrate this, they develop real compassion. Empathy is not a technique, it comes from understanding suffering. We need to deconstruct this instrumental approach to intellectualized and learning empathy as a technique. In Buddhist Asia, there is a strong sense of karmic determinism, in which people have internalized trauma as self-blame due to some bad act they must have done in a previous life.

Buddhist Psychology: Clear Blue Sky

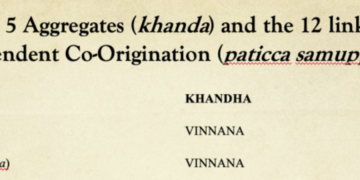

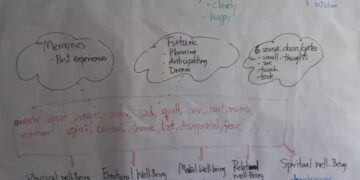

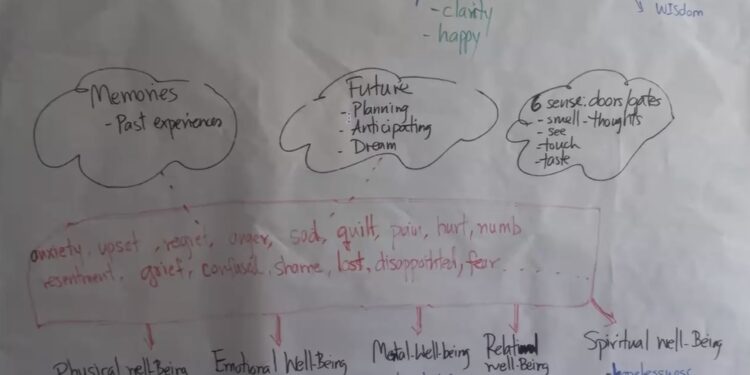

Tenzin Palmo’s and Sogyal Rinpoche’s are Tibetan teachers who have spoken about Buddhist psychology in simple way using the image of the mind as Clear Blue Sky or rigpa. I use this metaphor to develop a Clear Blue Sky framework. This clear blue sky is bodhi-citta or “buddha-mind”. It is vast, fresh, peaceful, happy, clear, and luminous. Yet the sky is not always clear. There are many clouds coming from the past, the future, and the 6 sense doors. I work with people to develop a sence that it is normal that these clouds are always present.

We have developed an empowerment model. This starts with 1) being a witness of others suffering through “deep listening”. People actually don’t need advice. They just need someone to listen and witness them. What is most difficult is their sense of shame, guilt, and fear. For example, social activists from Myanmar have a lot of guilt.

Body centered meditation practices help a lot with this problem. You listen to their suffering with the body and breath. This creates a safe space and a container to hold the suffering non-judementally. Being with the suffering is the hardest part of being a helper, but I find that after 15-20 mins of deep listening the speaker relaxes.

If the case is very severe, I just work to help the person let the suffering out and to reflect what they shared without me adding anything. The “visceral feeling”, which in Buddhism is known as vedana-khandha, is the locus of the suffering. So then we 2) name this visceral feeling and then look at what causes the more complex mental and emotional feelings.

There are other layers that come out with deep listening. Then, 3) you try to identify the power within that you genuinely see in the person. This counteracts the shame, guilt, and regret. This also replaces the impulse to tell them what to do. Next, you 4) ask questions that help them reflect, “How can you find the power that will help you transform this trauma?” Trauma survivors know what to do. They just need a mirror to be there to show them their strengths. Asking questions is not about what we want to know but about what we want them to understand about their internal world.

Then, I conclude by 5) trying to support the individual as best I can to experience the various dimensions of wellbeing and engage in self-car techniques. I and my partner Ginger Norwood have developed 5 dimensions of wellbeing to support burnt out feminist activists. These 5 dimensions are: relational, mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional. Then we look at something you will do, something you will stop, and something you will start. In terms of collective trauma, like survivors of the war in Myanmar, I have found that it is better to work in a group, but not more than 14 persons.

Group DIscussion

Question: In my prison chaplaincy, I find the same culture. The connection you made between understanding and compassion reminded me of the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh. It was inspiring to hear you say that its normal to have troubling thoughts and also the way you move toward identifying strengths. This is important in dealing with children who often put the blame on themselves. I see a lot of young teenagers in the nighttime suicide chat line I do here in Sweden. The question is how to empower children and women in these situations?

Ouyporn: Naming the abuse that is going on is an important method. The abuse is also coming from the culture, especially in Asia where you feel you cannot express your pain or seek for help. Being a good mirror involves reflecting these cultural layers and the trouble that it causes. We need to be the first adult that a child can trust, that is key. From there it can be expanded to larger safe spaces.

Question: A lot of the trauma comes from institutional aspects. Is there an integration with these institutional systems? How do we navigate through these institutional frameworks?

Ouyporn: Yes, we must work with the family too, otherwise the problem will just keep coming back. Psychology in Thailand focuses on mental illness. In contrast, I find the word “wellbeing” is very positive and well received here. The stress and intensity of life is what leads us to trauma, and “mental illness” is a dismissive term. So wow do we name experiences to make them more inviting. I hope to write a book about language and power in Thai someday. With a 5-7 day training workshop, a community forms organically. These kinds of workshops build family, while modern clinics are quite individual in focus.

Question: Could you share more with us about structural oppression and structural violence?The teaching of karma is twisted and misunderstood. It is used for oppression sometimes. During COVID, there was a survey done in Japan, China, Italy and the UK of what people thought about those who contracted COVID. An unusually high number in Japan said it was because they did something bad in the past. We can find in the ancient Pali texts that the Buddha said you can never know about other people’s karma. Unless you are enlightened, you can never tell what causes what in other people. As a Buddhist, you should never talk in this way. But in Confucian ideas of filial piety, you cannot talk badly about your parents, and this culture is still very strong in East Asia. We need some activities that can lead to changing the perspectives on these structural and cultural aspects.

Ouyporn: I built two temples and started my center all because of the problems in Thai culture stemming from these issues. I used to hope that famous monks would speak out on it but few do. Wellbeing and social movement building always need to go together. The meditation retreats and centers in Myanmar are not supporting people’s experiences. Further, there is a gap with the practitioner monks who focus on mind and are not connected with bodily experiences. Wellbeing is a strategy, and you need it to strategize an effective movement. I am challenging social activists to deconstruct activist culture and the feeling they always have about not doing enough. When you do wellbeing it has be organizational wellbeing.