from physical comportment to psycho-spiritual balance and insight

1) Does one keeps their eyes open while meditating and how to teach this

- Teaching with eyes half closed is standard in Buddhism, but this is difficult for beginner students unaccustomed to it. It helps to avoid the tendency to wander off in thought or visual fantasy with eyes completely closed, yet still provides a sense of inner space and reflection. With eyes half open, one also maintains a sense of being in the present physical space that provides a further rooting to mindfulness. To help students struggling with this technique, you can put a burning incense stick in the middle of the floor which they can gaze at as their sight line comes off their nose. Students may also put any random object on the floor, like a set of keys, to do the same.

- In the Shambala tradition of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, we teach to keep your eyes open and gaze 3-6 feet in front of you, because Trungpa Rinpoche wanted to integrate awareness with the phenomenal world. We acquire a lot through our eyes and there is a lot of grasping. So if you have a lot of thoughts, you pull the gaze in closer. Basic meditation is gazing outward but not looking at anything in particular. At some point, the gaze can be raised out to the horizon. Anything can be a focal point for meditation, but the breath is the key focal point. If you are trained with the eyes closed, you are in an internal world and disconnected from the sense of the eyes. If you train with the eyes open, it is much easier to train with the state of awareness in an integrated way. Doing one or the other can change the state of awareness. There are different kinds of meditation in Tibetan Buddhism that require the eyes to be shut, such as working with the body’s energy channels, seed syllables, and so forth.

- In the Thich Nhat Hanh lineage, we learned to meditate with eyes closed. Thich Nhat Hanh did not speak so much about liberation. He wanted westerners to learn to simply settle down. In contrast, in the Shamabala tradition, the emphasis on keeping eyes open seems like a simple idea in which awakening is practiced with the eyes open. Trungpa Rinpoche also speaks about being tight yet loose at the same time. Visual fixation is easier to notice while meditating with the eyes open, and one may notice, “Oh, I am looking at something now” as well as noting what is the difference between seeing and looking. In psychotherapy, there is a lot of somatic observation of the body, since many clients are dissociated from their bodies. Noticing the jaw and lips and then how the esophagus and shoulders open during meditation can be helpful.

- In Soto Zen training, it can be helpful to keep the eyes closed for a few minutes to help the body and mind relax before reopening the eyes. Keeping the eyes open is about not escaping, but some use open gaze to escape things coming up internally. In traditional Zen, the eyes are kept half open. This is to keep the mind in the present moment, like a ship with an anchor down; even during a storm the ship will not be swept away. The pattern on the floor can also be used as a focal point. Zazen is usually done in a dark room. After some years of practice, the practitioner may be allowed to close their eyes sometimes. Further, it is much easier with the eyes half open to develop a good body posture with open and straight shoulders.

- Posture and keeping the eyes open are also key in the Chinese tradition. There is a way of sitting with a sense of entirely relaxed muscles. The organs sit in place over the bones and the head above the shoulders so that everything else releases. We want the head to be resting over the shoulders. We also want the shoulders to be fully relaxed. Let the arms hang and then place the hands where they need to be.

2) The issue of posture

- The Taoist based tradition of Qi Gong emphasizes a very straight spine to allow the vital energy to move up the spine and then down the front. Posture is not so emphasized in Theravada practice. But from both Zen and Qi Gong, posture is a very important part of meditation teaching. Good posture helps to ground the mind as one struggles to develop mindfulness and insight.

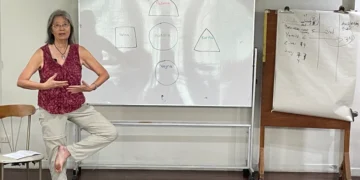

- In Soto Zen, there is a strong focus on posture from the start. The Christian church seems to start with words, but in Zen they start with the body. Using the metaphor of a string at the top of the head to straighten the spine and neck is helpful but this and tucking in the chin can also create a lot of tension. One also needs to relax into the upright posture. Roshi Joan Halifax’s phrase “strong back and soft front” is a good reminder. In terms of this metaphor, if we are too soft, then we crumble; a downregulated system is hunched and sunken. If we are too strong, we are closed and very rigid; an upregulated nervous system is very erect. This is a very effective and accessible way of communicating to non-Buddhists. The spine is naturally curved and is protective, but it is also crunching our organs, making us less alive. If we can learn to be not too upright, then we find there is naturally the soft front and strong back. If we allow the natural curve, we can be bidirectional. Then we can settle into the support beneath us while moving upright into openness. There can be a tendency for practitioners to pivot too far. It’s more about modulating our awareness for the right context; with friends and with meditation, there are different postures.

- Some good references are Sitting: The Physical Art of Meditation by Erika Berland and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment by Pat Ogden and Janina Fisher. Will Johnson is the founder and director of the Institute for Embodiment Training, which combines Western somatic psychotherapy with Eastern meditation practices, and he has taught extensively about posture in his The Posture of Meditation and Breathing Through the Whole Body. Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing: How to Gain Direct Access to Your Body’s Knowledge and David Rome’s Your Body Knows The Answer may also be helpful resources.

3) The attitude towards meditation

- There is also the attitude of posture, a sense of wellbeing, and the perfect emotional balance of the Buddha sitting in meditation. A soft front means an openness to the world, while a strong back is the resilience to be in the world at the same time. This connects to the way Dogen taught zazen as not a means to gain enlightenment but a way to manifest it right now. A meditation space should feel safe so that one can sit beautifully straight and open, manifesting their own buddha nature and not trying to become like an idealized version of someone else’s enlightenment, even the Buddha’s.

- Meditation can be seen as a vulnerable position because you are sitting quite defenseless. You open yourself up to many layers of suffering by practicing the 1st Noble Truth and composting or allowing the suffering to ferment into the 2nd , 3rd and 4th Truths. It takes strength to be vulnerable. Through this work, we feel more open and capable of sharing. Roshi Halifax calls this “empathic distress”.

- What if we don’t take the object of mind as content but take the relationship between the mind and its experience as primary instead? What kinds of relationships are built up between the mind and its objects of awareness? In this way, we learn to have a choice of how to relate. We can’t change the object, but we can adjust the relationship to it. This is related to the practice of Focusing, developed by Eugene Gendlin. Suffering is just a phenomenon that we pay attention to, so the question may develop, how do we pay attention? Through this process, we learn how to change.

4) Focusing vs. Mindfulness & Insight Meditation (vipassana)

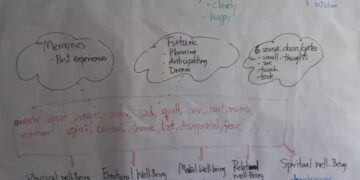

- Focusing is a somatic type of meditation to look into the deep emotions. For those that still have serious hangups but are deep practitioners, there needs to be a new technique. Mindfulness in itself does not cover this, so Focusing is an interesting development. Eugene Gendlin developed a system that asks, “What is the real factor or sign that indicates that the client has been helped?” He found that only those that could speak about somatic effects were really helped. Unless the client did not come back to their body, they weren’t sufficiently “helped”. Gendlin developed a new model that is beyond verbal processes. The counselor does not develop the process, rather the client does. If the therapist invents the verbal sytem, it can violate the client’s unique situation. This preverbal recognition is more fundamental than the verbal state. When we use language, we are already repressing something. The somatic location (head, heart, gut) can also provide important understanding.

- Open Focusing is more related to meditation, since the inventor, Les Fehmi is a Buddhist practitioner. The key factor is practicing sati (mindfulness) by keeping open awareness to any information from six-doors of consciousness. (See Les Fehmi, Susan Shor Fehmi‘s The Open-Focus Life: Practices to Develop Attention and Awareness for Optimal Well-Being). Fehmi just used a new method to gather the wandering mind to bring the awareness to the space between emptiness. Open Focusing is a very helpful technique. It begins with balancing and then shifts to the breath. By paying attention to “emptiness” (sunnata), one doesn’t attach to anything and then shifts to the breath. One rests in space without grasping any object, shifting attention then to the present task. This is a kind of mindfulness through a neurologist’s approach. There is no need to use language, just go directly to the somatic process.

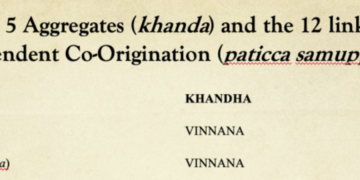

- Buddhism has a similar practice in the “insight meditation” (vipassana), which is understood, interpreted, and presented in a variety of ways in the Theravada tradition. One way is to pay attention to the location of the sensation, then goes inside to feel the color, message, and words that arise. Then one can ask, “What does that mean to me?” In vipassana, the key is to see the arising and perishing of the phenomenon. Another way is through observing the arising of the five aggregates (khandas): being rooted in one’s posture and physicality (rupa), one observes the arising of a specific sense consciousness (vinnana), then its visceral feeling (vedana) as positive, negative, neutral, followed by a variety of perceptions (sanya) like hot, sharp, nauseuous, itchy etc. and then finally the development of cognitive thought (sankhara) with opinions and fully formed emotions. One not only learns to recognize patterns of thought but also pre-verbal areas of experience where traumatic patterns of response may be ingrained. Yet another way is to just pay attention to the sensation. Don’t ask which story is related to this sensation. In Buddhist vipassana, the story is not taken into account. The purpose is to see the aggregates (khandas). The Importance of Vedana and Sampajanna is a book that is helpful in discussing the difference between the contemplation of feeling (vedana) and Focusing in terms of whether one will trace the memory evoked from the sensation or not.

- The story is found in the investigation of the 2nd Noble Truth which continually pushes us to look more deeply. One tends to find oneself bumping up againt blame, either of oneself or others. But Buddhism steers us away from blame, directing us to the experience of not-self, emptiness, and the total interconnection of phenomena; who is there to blame? So one keeps pushing deeper and deeper until states of wisdom and compassion arise naturally, instead of thinking you’re going to figure things out and get a definitive answer from the cognitive mind.

- Trungpa Rinpoche would emphasize that by creating greater space, solutions will appear. He taught that there is no goal, just a process; the path is the goal. Buddhism teaches about going beyond everything, but for ordinary people, we are usually just stuck in what we are in. In this way, Buddhist meditation seems to often be not about dealing with the traumas that we have here and now. Building bridges between the more transcendental or spiritual dimension of Buddhism and the more phenomenal ones of neurobiology and psychotherapy is important today. In this way, Focusing and vipassana can be used in a complementary way.

- Buddhism is so much more than meditation, which many westerners have reduced it to. Ethics (sila) and wisdom (prajna) are considered just as essential in what is known as the Three Trainings. You have practices like the 4 brahmaviharas and the 6 or 10 paramitas that are ethical but take aspects of wisdom and are also integrated into meditation practice. Prajna is also a prerequisite for meditation as well; discipline or sila is also a good way to develop a solid meditation practice. The traditions that are too focused on having an “awakening experience” lose site of other important aspects. This is what Trungpa called Spiritual Materialism.

- What does it mean for mind and body to be synchronized? Most of us are out of synch most of the time. When we synchronize mind and body, we cannot bypass. We think too much, so we are not in touch with our body and surroundings. The mind has become too strong. In meditation, dealing with the mind is the initial activity that needs to be done, taming the mind and not interfering. We deal with this, taking away the energy of thinking and directing attention towards the body or the sensations or breathing

- We have two minds: one that thinks and one that is the heart-mind 心 or enlightened mind bodhi-citta. The task is to synchronize the body and breathing automatically, first by adjusting body posture, then breathing deeply, and then adjusting the mind. Natural, metabolic breathing is related to the brain stem. Deep, conscious breathing over 20 seconds per inhalation or exhalation creates alpha waves and stimulates the cerebral cortex. In this way, practicing “moving zen” (do-zen) and and “sitting zen” (za-zen) trains the mind deeply to be less reactive. In the first 10 minutes, we take 10 second breaths, and then extend to 20 second breaths over the next 10 minutes. After 20 minutes, we may move into one minute breaths, with very light inhalation and exhalation. In Tai Chi practice, ther is an evolution from first moving hands with the mind to then moving hands with the waist, then eventually moving his hands with just the breath, which may take more than 10 years of practice.

5) How do we evaluate a student’s progress?

- We can start with what it is NOT about. In counseling, it’s not about helping people to feel better (this is also true in meditation). Making a murderer feel better through meditation would be spiritual bypassing, but relating directly to ethics (sila) will also not always work. I tell people that sometimes “the bad news is the good news”. Negative experience is the important information to work with.