May 28-31, 2024

Introduction

The Institute of Buddhist Counseling and Chaplaincy (IBCC) is a group of Buddhist chaplains, Buddhist based psychotherapists, and socially engaged Buddhists active in a wide variety of mental health issues. It evolved from rank-and-file Buddhist priests in Japan who had begun to confront the suicide epidemic in that nation in the early 2000s. In 2017, the group in Japan began creating international events with practitioners in both Asia and the West to pursue a deeper understanding of mental health issues and share various practices and techniques. At this time, an important linkage was created between Japanese and Korean suicide prevention activists to meet the suicide pandemic that both nations faced. With common social dynamics and cultural values, a rich dialogue has emerged, specifically in two areas: 1) how both local and national governments along with civil society groups and religious organizations are building public policies to confront the problem; and 2) how Buddhist priests and other religious professionals are confronting the issue as counselors for suffering individuals and as social activists for systemic change. In general, Buddhist priests in Japan have already developed a strong national network of grassroots activities working for the suicidal and the bereaved, which the Koreans have been keen to learn from. Korean activists are also interested to see how public policy has developed over the past two decades in Japan since an policy approach that includes civil society and religious professionals is still weak in Korea. From this basis, members of the IBPC developed a four-day study tour of Japan for thirteen Korean activists from May 28-31, 2024, which was followed in August by a delegation of Japanese Buddhists and suicide prevention activists to Korea. The following report covers three main components of the May study tour as follows: 1) a half day symposium at the Kodosan temple in Yokohama of national and regional governmental experts on suicide prevention, leading Buddhist priests in the movement, and the Korean delegation; 2) a one day study visit to Yokosuka City in southern Kanagawa prefecture to learn how Buddhists are working closely with the local government on a holistic response to the problem; and 3) a one day study visit to Kyoto of Buddhist based suicide prevention activities supported by the Kyoto City government.

Symposium at Kodosan Temple

The delegation from Korea was welcomed to Kodosan temple by its 3rd President, Rev. Shojun Okano, who has been a central leader in IBCC since its founding. Kodosan also hosts the International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC) which has taken an active role in the building of the national Buddhist suicide prevention network in Japan since 2007. With a mandate for international exchange, it has provided an important bridge for suicide prevention priests and activists in Japan with like minded persons in Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

Present Issues and the Situation of Suicide Prevention Measures in Korea

After Rev. Okano’s opening message, the Korean delegation led by Prof. Cho Sung-Chul, Chairman of In Ae Welfare Foundation, and Mr. Park In-Joo, Chairman of the Headquarters for the Sharing Campaign also offered their greetings. The delegation consisted of 11 women and men involved in the movement together with 2 translators. They came from a variety of civil society organizations and included members of the Christian church as well as the Buddhist community. Pum-Soo Lee-a professor at the Graduate School of Buddhism at Dongguk University and a board member of the Buddhist Counseling Development Center-had presented on these issues at the 1st International Conference on Buddhism, Suicide Prevention, and Psycho-Spiritual Counseling also hosted at Kodosan in 2017, and he served as the main coordinator of the delegation.

Rev. Dae Sun, Won Buddhist minister and Permanent Representative of the United Religions Initiative of Korea, gave a summary of the key issues of suicide in Korea. In short, the suicide phenomenon in Korean society rose sharply from the pre-currency crisis suicide rate of about 12.7/100,000 persons in 1995 to a peak of 35.3 persons in 2009. Although it showed a slight downward trend to 25.2 in 2022, it has still remained in first place for nineteen years among the member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), except for one year. For comparison, Japan’s pre-currency crisis rate was 17.5 in 1995, reaching a peak of 24 in 2003 and then resting at 17.5 in 2022. On a standard population basis, the Korean rate of 24.1 in 2020 was 2.4 times higher than the average of 10.7 in OECD member countries and more than 1.5 times higher than the average of 15.4 in Japan. The number of suicide deaths in Korea in 2022 was 12,727. The causes ranged from: psychiatric problems 5,011 (39.4%), economic difficulties 2,868 (22.5%), physical illness 2,238 (17.6%), family issues 685 (5.4%), workplace or work related problems 404 (3.2%), gender relation problems 256 (2%), bereavement 105 (0.8%), and others 377 (3%).

Rev. Dae Sun explained that the economic dislocations of the 1990s led to the rapid dismantling of traditional family communities, dishonor, unemployment, joblessness, job insecurity, growing wealth disparity, and high divorce rates, all of which were caused by earlier trends toward materialism, fierce competition, and individualism. In this way, Rev. Dae Sun emphasized that clinical interventions, such as relying on psychiatric medication, targeting only suicide risk groups are unlikely to have a significant impact on reducing suicide rates. This has been a problem in Korea where medical associations and doctors have dominated public policy development. A public health approach that eliminates and manages the various socioeconomic factors associated with suicide may be a more effective way to reduce suicide rates by targeting the general population and addressing the various factors that cause suicide. Multiple interventions can rapidly reduce suicide rates.

The suicide rate in Korean society over the past 30 years has begun to show a faint outline of a way out, as the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Korea Foundation for Life and Hope (formerly the Central Suicide Prevention Center), the Korea Association for Suicide Prevention, religious organizations, civic groups, and various other sectors have worked hard to lay such a groundwork. Rev. Dae Sun warned, however, that no matter how effective a national suicide prevention strategy is developed by the central government, it will not produce results unless it operates within the community in the context of that strategy. The World Health Organization (WHO) specifically emphasizes local government leadership and the establishment of voluntary suicide prevention plans, because communities are the best place to identify and respond to their local needs and priorities. Rev. Dae Sun concluded that based on the Japanese approach, if the central government establishes appropriate basic policies and local governments more actively and systematically formulate and implement suicide prevention enforcement plans that take into account the psycho-socio-economic context, Korean society will be able to pull itself out of the suicide quagmire.

Public Policy and Governmental Responses to the Suicide Problem in Japan

Following the Korean delegation’s presentation, three speakers from the national and local governmental levels spoke on public policy towards suicide prevention in Japan. The first was Prof. Tadashi Takeshima, Director of the Kawasaki City Comprehensive Rehabilitation Promotion Centre, representative of the National Liaison Council for Mental Health and Welfare, and former Director of the Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Center, which was in charge of national suicide prevention. In general, Buddhist priests and other religious professionals have been deeply marginalized from social work in the modern era due to the rigid interpretation of the policy of “the separation of religion and state” (sei-kyo bunri) and many governmental officials, medical professionals and academics have little interest in working with them. Prof. Takeshima is very different and has developed a strong relationship with Buddhist suicide prevention priests, while also speaking at IBEC’s first international conference in 2017.

Prof. Takeshima’s talk focused on his recent research around the history of suicide after World War II. One of the main issues that is lacking in suicide prevention work in Japan is a deeper analysis of structural violence and cultural issues that have given birth to this pandemic. War trauma is one of these issues as the Japanese response to the trauma of the defeat in the war set off a series of social trends towards workaholism, materialism, and the repression of spiritual and psychological needs. Prof. Takeshima’s research is thus a welcome development in the deeper examination of causes, in line with the Buddha’s teaching of the 2nd Noble Truth of the causes of suffering (dukkha). In short, there was a rapid increase in suicide in the 1950s, yet basic awareness and associations focused on the issue did not emerge until the 1970s and 80s. Another surge in suicides began with the Asian currency crisis of 1997-98 that also deeply impacted Korea. In one year, the number of suicides in Japan jumped from 23,000 to 32,000. At this time, suicide was generally regarded as a personal, individual problem connected to depression and mental illness. In 2004, Japan’s most important civil society suicide prevention organization, LifeLink, was founded. In the following year, in collaboration with the Federation of Japanese Life Lines and twelve other private organizations, they issued a comprehensive report on the suicide issue that described social causes such as overwork and broken family systems. In 2009, the government created the Emergency Local Suicide Prevention Fund to strengthen local suicide prevention capabilities. This led to a rapid spread of suicide prevention measures to local governments, and the number of suicides began a downward trend in 2009 with the number falling below 30,000 in 2012 for the first time in 15 years.

Prof. Takeshima pointed out, however, that various problems still exist in public policy. In 2019, the Law on Research and Study to Contribute to the Comprehensive and Effective Implementation of Suicide Prevention and the Utilization of the Results of Such Research was promulgated. This law creates designated research and study corporations and other necessary matters as part of the development of a system for the comprehensive and effective promotion of suicide countermeasures. After a public selection process, Lifelink (a.k.a. the Center for Suicide Prevention and Response) was designated as the main hub for determining where government support feeds into civil society. As a result, suicide prevention, which had been carried out by a variety of entities, is now under a system in which the national government and Lifelink as “the designated corporation” (shi-tei ho-jin) have significant authority. Prof. Takeshima emphasized that a shift is need to build a bottom-up scientific and impartial suicide prevention network through collaboration among local governments, interdisciplinary researchers, suicide survivors, and community supporters. The participation of suicide survivors in the policy-making process of suicide prevention is particularly essential to promote.

The second speaker was Mr. Kazuhiro Tsukada, Director of the Planning and Coordination Promotion Section at the Comprehensive Rehabilitation Promotion Centre in Kawasaki City. Kawasaki experienced a major jump in suicides from 12.0 to 16.1 in 1994-95 before the national spike in 1997-98. Before this, Kawasaki had been well below the national level. It experienced another jump along with the national one in 1997-98 to 23.2. A decline in 2001 to 18.6 went against national trends, yet again there was a gradual increase along with national trends to 22.5 in 2009. There was a major drop from 16.2 to 12.0 in 2015-16 but then a new surge with Covid to 15.8 in 2022, these figures all slightly below national average. Mr. Tsukada explained a wide variety of bureaucratic policies and measures that the Kawasaki government has undertaken in line with the vision “to create a safe and secure community and a society where people are not driven to suicide, in cooperation with schools, employers, local community organizations, and other diverse actors in the community around us.” He outlined a number of quantitative targets for suicide prevention, yet when he acknowledged the need for qualitative targets, he only posited a number of vague points such as, “Is there any room for improvement?”, “Is it necessary to make efforts to verify what measures were effective?”, “Are individual efforts losing their necessity, effectiveness, and efficiency?” and “Are we promoting comprehensive suicide prevention?”. A proper qualitative approach would include an analysis of problematic values that Rev. Dae Sun emphasized such as “materialism, fierce competition, and individualism”. The overall bureaucratic style of the Kawasaki City government’s approach also strikes right at Prof. Takeshima’s criticisms of public policy that use vague, technical terms and do not sufficiently include the voices of the suicidal and other stakeholders. While Mr. Tsukada did emphasize the now common attitude that suicide is not an individual problem but one that needs to be addressed by society as a whole, he also stated that “not only the government, but also citizens must reevaluate suicide as their own problem, not someone else’s”. The apparent gap between the goals and the approach shows that there is still a strong need for an increased democratization of the process where the government develops a better system for representing the voices and needs of its citizens.

The third speaker was Mr. Hideaki Matsuki from the Office for the Prevention of Loneliness and Isolation in the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister of Japan. His participation was very welcome and a bit surprising as the central government has an even stronger distaste of and bias against religious organizations and taking part in events sponsored by religious groups. This symposium was thus an indicator at how much socially engaged Buddhist work in the area of suicide prevention has helped to re-establish Buddhist priests and organizations as important parts of Japanese civil society. The title of not only Mr. Matsuki’s department in the Cabinet Office and his talk—“The rebuilding of loose links between local residents, which have been lost in today’s Japanese society”—indicate a deeper level of awareness of the problems in contemporary Japanese society. The government, corporations, and politicians are often loath to look at these deeper issues as they threaten the status quo. However, the collapse of Japan’s miracle postwar economy and its unique family-based corporate culture have become undeniable. The need for a new social vision and paradigm for 21st century Japan is urgent.

Mr. Matsuki indeed recognized these deeper structural and cultural problems in his talk, such as, increases in precarious employment, single-person households, school dropouts, and human disconnection. He also described the pair issues of “loneliness” (孤独 kodoku–a subjective concept that refers to the mental state of feeling alone) and “isolation” (孤立 koritsu—an objective concept that refers to the state of having no or little social connection or help). The former may happen to an elderly person living alone in the countryside, while the latter may happen to a single mother raising two children on her own and only being able to get part-time employment. From a national survey on the situation of loneliness and isolation done in 2023, about 40-50% of people said they experience loneliness in terms of lacking social contacts, feeling left out, and feeling isolated from others. 47.0% responded either “always” or “sometimes” to these questions. Mr. Matsuki then detailed a number of policies by the government to support non-profit organizations to work on measures to combat loneliness and isolation, emphasizing the need for public-private partnership. These initiatives include: creating inter-generational community centers, new types of cultural facilities and activities, and opportunities for the elderly to use their accumulated skills and wisdom for public benefit.

On the one hand, it is heartening to see the government trying to make more open and compassionate spaces for people in a society that, like Korea, became brutally competitive and intolerant to those with different viewpoints and lifestyles. In the question and answer sessions at the end of the symposium, Mr. Matsuki also expressed an interest by the government to work with local temples to revive rituals and art that help heal isolation and loneliness and provide peer support among at risk people. The re-interpretation of the separation of church and state to enable such vital collaborations is an important aspect in healing and moving on from the traumas of World War II that included the bankruptcy of its spiritual traditions. On the other hand, these initiatives began to seem like those of Kawasaki City, just focused on a different issue, “loneliness” instead of “suicide”. The tendency of government bureaucracy to isolate an issue into a series of targeted policy directives shows the limitations of modern, utilitarian government and the need for more decentralized social development, which as Prof. Takeshima emphasized is bottom-up, participatory, and interdisciplinary.

Buddhist-based Suicide Prevention in Japan

The next speaker at the symposium provided an important example of such a bottom-up, participatory, and interdisciplinary approach to suicide prevention. Rev. Yukan Ogawa is the abbot of Renpo-ji temple of the Jodo Pure Land Denomination in Fuchi City in western Tokyo. He became involved in suicide prevention as a research fellow at IBEC in 2006, and in 2008 joined the newly established Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide. He has also developed a close relationship with Prof. Takeshima, creating an important interdisciplinary link between religious professionals and academics on this issue. Rev. Ogawa explained the work of the association, which is a remarkable network of priests from a wide variety of different denominations. As a network, they provide an important source of information sharing and mutual self-care support for priests working as individuals in their own communities. As a collective, one of their main activities, which also serves as a way to train new priests to the work, is counseling the suicidal through intimate handwritten letters. The idea behind counseling by letter is to focus on the emotional tenor of the correspondent rather than asking questions. By writing a letter, the person may find it helpful through adjusting or rearranging the issues and slowly working through a complicated matter. With the letter always available for reference for the client, the association hopes to provide a sense of warmth for them at anytime. Furthermore, by using traditional Japanese brush pens, a certain emotional subtlety and state of mind can be expressed between the priest and client that may be helpful. The goal is to support them to regain their footing by their own power. By the end of 2019, the association had responded to a total of 8,369 letters over an 11-year period from 1,448 people (1,194 women, 254 men) from all over Japan by 42 priests.

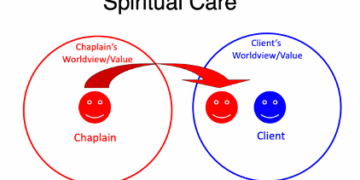

Rev. Ogawa also explained that it is important in the work of religious professionals to prevent suicide to not take the stance of trying to treat or cure people, but rather to accept them as they are. The priest needs to serve as a refuge and to provide a place where people can escape the common values of society. Bereaved families are often unable to speak about the suicide of an important family member, so they suffer in a special kind of silence. Society has many prejudices against the suicidal, so it is important for bereaved members to gather together and share their feelings. They began such gatherings in June of 2009, and from October 2018 to September 2019 the average attendance was 38 persons per month, an increase from 25 persons in the same period between 2015-2016, for a one-year total of 462 persons (102 of which were newcomers). Of those 38 persons per month, about 8 were newcomers.

The group also holds a special memorial service once a year for around 150 participants. Due to various reasons, many families do not gain any satisfaction from the funeral of their suicidal loved one. Families may also have become divided with other relatives who have criticized them. There are few opportunities to provide any care as the funeral becomes a place of suffering. From the written reflections received at the end of these special services, they have been able to understand how families have made a connection with the departed loved one, for example, “I was able to express my thoughts to my father.”; “Although it was brief, I felt I could meet with my daughter again.” By offering a place to mourn, people can make a connection with the deceased and recall them in ease without the discrimination attached to suicide. The impact of the association is evidenced by the spawning of other such regional associations in Osaka and Nagoya in 2009, Hiroshima in 2013, and Kyushu in 2014.

Its impact as a bottom-up, grassroots movement has also been duly noted on the conservative headquarters of many denominations. The last speaker of the symposium—Rev. Zenchi Unno of the Soto Zen Center for Comprehensive Studies—spoke of this influence and the attempt to develop suicide prevention and psycho-spiritual counseling skills among all Soto Zen temples in Japan. Rev. Unno has been involved in the planning and management of workshops to train Soto Zen priests in counseling and in the conducting of memorial services by the Soto sect headquarters for the bereaved families of suicides. He explained that the traditional Buddhist denominations of Japan do not seriously confront people who are dealing with anxiety and depression. The contemporary image of Buddhism in Japan is that of temples and priests focused only on funerals with the pejorative name Funeral Buddhism (soshiki bukkyo) being coined. This image has further pushed Buddhism out of the public sphere and out of the mind/hearts of many Japanese. As such, there has been an urgent need for the traditional denominations to begin a process of critical self-examination and rediscover the core meaning of the Buddhist priest and temple.

One important activity in such a process would be for temples to engage in counseling for those in suffering. Rev. Uno noted that in the way one has a regular family doctor, one should have a regular family temple, where one can come to first with any kind of anxiety or insecurity to speak with the abbot or his wife/their partner who offer “presence” and “deep listening”. However, this is not so simple. The words that one thinks are right for someone to hear may actually hurt them. A Buddhist priest has much pride in their ability to sermonize, yet their weakness is in listening to what others have to say. The Soto Zen denomination has created a study and training curriculum for the purpose of “facing life”, which roughly 5,500 priests and 2,500 temple wives in 50 centers around the country have participated in. The focus is not just on academic study for giving dharma talks but also providing experiential training, which includes consultation through letter writing.

A third important role that priests can take on is what is called in Japan as a “gatekeeper”, that is a person who offers a window or entry point for the support of people with depression and anxiety. Because a priest is there for the traditional memorial services that take place soon after the death, they are often able to properly ascertain a family’s makeup and situation. On the other hand, workers at public health facilities often say that, “We know that there is a high risk of suicide among bereaved family members, but they have a hard time coming to us about it.” In this way, there is great potential for the priest to take on the role of a “gatekeeper”. In conclusion, Rev. Uno expressed his hope to connect the ideal of the Buddhist practitioner to heal suffering and offer peace with this restoration of the family situation. In order to be a true Buddhist priest and also in order to realize the function of the temple, he thus feels that it is important that priests get involved in the problem of suicide.

Suicide Prevention at the Community Level in Yokosuka City

To directly experience many of the ideas and activities presented at the symposium at Kodosan, the Korean delegation was taken the next day to Yokosuka City, about an hour south of Yokohama. There were hosted by Rev. Soin Fujio, the abbot of Dokuon-ji temple of the Rinzai Zen denomination. Rev. Fujio is not only one of the leaders of the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide profiled by Rev. Ogawa, he is also a gatekeeper, as explained by Rev. Unno, at the Yokosuka City Hall. Having started this work in 2014, he is one of the first and most prominent examples of a suicide prevention priest taking on an official role in a local government office. Since this time, he has also moved into positions in the wider Yokohama and Kanagawa areas, such as the Kanagawa Prefectural Bureau of Health and Suicide Prevention.

From this basis, Rev. Fujio invited the Korean delegation to the Well City Civic Plaza of the Yokosuka City Public Health Center to see how this locality works on suicide prevention. With a population of 371,930, Yokosuka City also hosts one of the largest American military bases in Japan. While incidents with U.S. soldiers have not been as severe as those in Okinawa, the existence of 25,000 military personnel and their families is a constant reminder of the war trauma of the past as well as the challenges of becoming a multi-ethnic nation in the future. The responsibilities of the Yokosuka Health Center go beyond suicide prevention and attempt to handle a wider range of issues regarding mental health, such as “extreme social withdrawal” known as hikikomori and addiction to alcohol. In a nation with very little recreational drug use, the common attachment to alcohol is not often recognized as a matter to be handled outside of the home. Like Kawasaki, Yokosuka has a number of mental health promotion and suicide prevention activities in line with their motto of “Creating a City Where No One Is Left Alone”. Also like Kawasaki, much of the support seems highly bureaucratic in which persons at risk are identified after being admitted to two local hospitals where they are asked to fill out a Suicide Attempt Survivor Form. While the city seemed to be making some headway between 2010 and 2017 with the number of suicide attempt survivors who consented to receive support increasing to a peak rate of over 50%, beginning in 2018 the rate began to drop to the 40% range and then down to 34% in 2022.

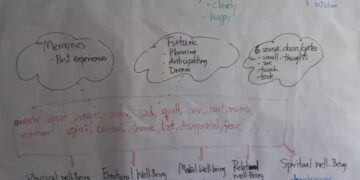

Again, we are called to see this issue both more expansively and more deeply than just a problem of “suicide” or even “loneliness”. Rev. Dae Sun earlier mentioned a wide range of both structural factors and cultural ones representative of a wider ranging problem in the fundamental fabric of modern, capitalist society. In nations all over the world, suicide has been on the rise as the values of competition, comparison, and convenience dominate our daily consciousness. Another member of the Japanese Buddhist suicide prevention priest community is Rev. Jotetsu Nemoto, a Rinzai Zen priest who grew up in Tokyo but now lives in rural Gifu. He has expanded his earlier work in “suicide prevention” to a broader sense of rebuilding human connection and community. He has formed a group named Ittetsu Net, which he calls “a network for building friendships and for holding workshops for mental and physical health, emphasizing self-care and outdoor activities.” A typical event will be a collaboration with a yoga teacher in a park to practice yoga and meditation. Participants are not gathered just from Rev. Nemoto’s network of suicidal clients. He feels this would defeat the purpose. He wishes not to make such a clear-cut demarcation between the suicidal and the non-suicidal—for the line between them is actually not so distinct—and to further get away from people feeling stigmatized because of being suicidal or mentally ill. Through his years of work, he has found the prevalent model of volunteers and counselors working in a one-way relationship with the mentally ill and disturbed does not work. Eventually, the former get tired and burned out, and the latter find they cannot receive the answers they are hoping for. A downward spiral ensues with the waning commitment of caregivers and the disillusionment of patients—as perhaps witnessed in the declining rate of catchment in Yokosuka of such persons. In Ittetsu Net, Rev. Nemoto seeks to build a more dynamic framework of interaction in which a variety of different groups are united in the central ideal of self-care. In these activities, people enjoy themselves in a more playful manner, which then draws in an even greater diversity of people. Within this dynamic container, Rev. Nemoto recounts, counseling will take place naturally at these events. In this way, Rev. Nemoto is working on getting deeper at the roots of the suicide problem in Japan by shifting his focus from helping specifically suicidal people one-on-one to working with groups of people sharing a wider range of anxieties, and then working to build back communities of “connection” (en) based around healthy living.

Returning to his fellow Rinzai Zen colleague, Rev. Fujio, the Korean delegation visited his nearby temple in the afternoon for some experiential learning. Dokuon-ji is a temple with long standing roots in the community, and Rev. Fujio learned much about working with others from his father. As opposed to identifying the suicidal after the fact in hospitals, the community temple serves as a natural preventive “safe place” for people to visit when life has gone sideways. While the modern image of Buddhism in especially dense urban areas is a place concerned with funerals for its own members, in more rural areas, temples may still hold the trust of the community as sanctuaries. In this way, Rev. Fujio recounts that sometimes he opens the temple gate in the morning, and someone is waiting there. The catchment and support rate of Rev. Fujio who basically is available 24-7 appears then to be not only higher but more substantive than the Yokosuka City suicide prevention hotline, which only has enough staff to operate from 4:00 pm to 11:00 pm on weekdays and 9:00 am to 11:00 pm on weekends and holidays.

When Rev. Fujio greets such a person at his temple, they often look pale and either cannot talk or talk too much. This kind of depressed person is what he describes as about 50 notches below the normal state of functioning. His first task is to engage in deep listening without talking. Then, he attempts to go down into that place of depression through tuning his feeling to their level, meeting the person where they are. He notes, “When I am able to attune myself to the feeling inside a person’s mind/heart (心 kokoro), I try to touch the buddha inside them. This is what we call in Buddhism as ‘buddha-nature’ (仏性 bussho) or ‘enlightened heart/mind’ (bodhicitta 菩提心 bodaishin). I try to help them feel that they are not alone, so if something happens, I try to help them solve it.” This may take a while he says, but when he gets to their level, there is a feeling of real connection being made. Slowly, the person begins to respond and visible change may occur, such as an improvement in their complexion. It is only at this point that Rev. Fujio begins to speak to them with his own ideas and invite them to ascend with him out of their depths. If they get up to around the normal, neutral point of zero, he may invite them to do seated Zen meditation or other forms of Zen, such as with movement, as Rev. Fujio is also a highly accomplished Taichi teacher. At this point, they will start to ask him questions about what they can or should do. He may offer some kind of answer, though he feels there is no real “right answer” and encourages the person to think together of a solution. However, he says that he usually does not go this far during the first few visits with someone and instead just tries to attune to their feeling. In the initial encounter, this process will take about one to three hours, and Rev. Fujio reports that he has even sat with someone continuously for eight hours. Typically, one person will visit him up to ten times, sometimes every day in the beginning or once a week.

With a foundation of counseling activities at his temple that includes regular Zen meditation sessions for foreigners, businessmen, and medical professionals, Rev. Fujio developed the trust of local government officials who sought his support in developing social programs for the mentally ill and “disconnected” (mu-en). His first engagement was to run a group counseling session (wakachi-ai) for the bereaved once a month, like the ones with the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide, at the Yokosuka City public health center. Most recently, Rev. Fujio has also become more engaged in end-of-life care work. During the Coronavirus pandemic, his regular Saturday evening zazen sessions were conducted on zoom, and this allowed some participants who were in hospice or dying at home to participate. Also during the Corona era he met a man who had dropped out of corporate life to devote himself to Zen practice that helped him develop virtual reality Zen meditation and counseling rooms. Rev. Fujio has found that for depressed persons taking on new self-images with avatars can help them find new ways of imagining their lives and reviving their will to live.

In conclusion, Rev. Fujio and Yokosuka City provide numerous essential lessons in comprehensive suicide prevention work: within Buddhism itself, we see the importance of reviving community temples and retraining priests in the art of psycho-spiritual care, which is the “birth right” of all serious Buddhist practitioners. At the level of public policy and health, such temples and priests can provide essential “staff” to expand support for the mentally ill and suicidal. Yet, more importantly, the Buddhist view of holistic health, which includes body as well as mind, can help shift the compartmentalized view of health endemic to modern, bureaucratic systems. From a deeper understanding of the causes and conditions of ill-health or dukkha (the 2nd Noble Truth) comes a wider vision of what life and society could be. While we have seen that national and local governments in Japan are trying to embrace such a wider vision, Buddhist and other spiritual/religious viewpoints can provide much clearer roadmaps to such a vision that can provide essential aspects to public policy.

Buddhist Suicide Prevention in Japan’s Ancient Capital

Reviving temple and priestly roles in Japanese society would indeed seem appropriate in the ancient capital of Kyoto, visited by millions of tourists every year for its grand Buddhist temples and rich Buddhist culture. The Korean delegation journeyed to Kyoto for a one-day study tour of important Buddhist suicide prevention activities there. Out of the largest Buddhist denomination in Japan, the Jodo Shin Pure Land Hongan-ji denomination, has emerged another grassroots initiative by priests concerned with the suicide pandemic. Sotto, the Kyoto Self-Death & Suicide Counseling Center, was established in 2010 by ten priests from the Hongan-ji, one of whom, Rev. Sei Noro, met to explain their work to the Korean delegation. He explained that as individual Buddhist priests began to get involved in the suicide issue in the mid 2000s, one of the biggest barriers they faced was the damage caused by their fellow priests towards the families and loved ones of those who had committed suicide. Many discovered that one reason families were withholding the details of how their loved one had died was the high number of priests who would make pejorative comments or negative judgments about those who commit suicide. For example, “A person who throws away their life cannot rest in peace”, and “Since suicide cannot to be forgiven, such a person will fall into hell.” Another example involved a priest who refused to do a funeral for a child who had committed suicide unless the family paid an additional 500,000 yen to 800,000 yen, while still declaring to the family that the child could not be interred in the family cemetery plot located at the temple. Such publicized incidents led Rev. Noro and other members of the Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Research Institute to conduct a survey of their 10,281 affiliated temples on this issue in September of 2009. Among the 2,694 priests who responded, 68.7 percent said affirmatively that suicide is “an act of throwing away one’s life”. 74.1 percent responded affirmatively that suicide is “an act that goes against Buddhist teachings”. However, only 15 percent responded affirmatively that they had actually provided counseling to anyone who was suicidal. In short, Buddhist priests have a negative view of suicide derived from their respective sectarian doctrines, and the greater they hold this view, the less it seems they provide support to their lay members.

This research became the impetus to founding Sotto. At present, they have 48 regular members, 17 corporate members, 33 supporting members, and 25 monthly supporters with an annual budget of 10-20 million yen per year depending on subsidized projects and other contingencies. In 2012, Sotto began to receive public subsidies from the Kyoto City government for their work. The first such subsidized activity was a large public seminar in March 2013 on “Truly Confronting Suicide and Self-death” with panelists from a wide range of legal, governmental, and bereaved family support groups. This cooperative work between Sotto and the Kyoto government continues today with the latter providing consultation services for the start-up and management of suicide prevention groups, grants for a variety for related activities, and support for increasing private-public partnerships. In keeping within the boundaries of the separation of religion and state, Sotto does not advertise itself as a specifically Buddhist organization, yet the fact that it is staffed and run by Buddhist priests is also not hidden and easy to recognize. Thus, along with Rev. Fujio’s work in Yokosuka and greater Kanagawa, Sotto marks an important step forward in reviving the social role of the modern Buddhist priest and bringing a healthy form of religiosity into the public sphere. Further, Rev. Noro explained that the government also feels the need to consult with religious leaders, but there are few religious organizations even in the city of Kyoto that have a clear philosophy and are willing to work with them. As such, Sotto has become a resource for them.

The core staff is only 1 full-time and 3 part-timers, however, they have over 70 volunteer counselors from Buddhist, Christian, and Shinto organizations who have undergone training since the founding of the group. This volunteer staff includes housewives, Buddhist priests, graduate students majoring in psychology, and so forth. Some people who first came to them for support have subsequently become staff members. They provide telephone consultation on Fridays and Saturdays from 7:00 pm to 1:00 am (948 cases in 2022) as well as e-mail consultation 365 days a year with a reply from a consultant within 3 days after an immediate reply (2,434 cases in 2022). With such limited catchment, one discovers that one of their most important activities, like that of Rev. Fujio, is a face-to-face encounter in the sanctuary of a temple. And so the delegation was taken to a new site for an experiential learning session.

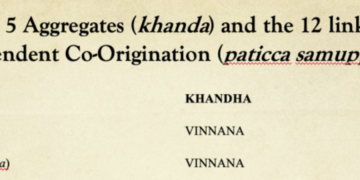

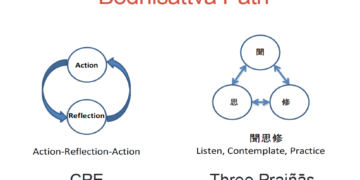

The approaches of Zen priests like Rev. Fujio and Rev. Nemoto to use the practice of Buddhist meditation as a foundation for interpersonal intimacy and resilient mindfulness in psycho-spiritual care is highly congruent with international trends in Buddhist chaplaincy. It is fascinating then to see how these Japanese Pure Land priests have developed an approach that is totally different yet quite congruent. They employ the Pure Land teaching of all humans, both ordained and lay alike, being deeply flawed and unable to access bodhicitta (菩提心 bodaishin) through their own efforts to attain enlightenment. Through the teaching of “other-power” and the inability to even liberate oneself much less anyone else, Pure Land priests understand the fundamental aspect of chaplaincy in which the chaplain does not provide answers but facilitates the discovery of them. Further, the literal meaning of sotto is “to sit quietly at one’s side”, which is congruent with the concept of “presence” (yori-soi) that modern Buddhist chaplains develop through the practice of meditative mindfulness. For the Pure Land priest, sotto involves a particular emphasis on providing the warmth they experience when embraced by Amida Buddha. As with the concepts of modern Buddhist chaplaincy, they seek to recognize and affirm the patient’s experience rather than negate it by offering their own solutions or viewpoints. Like Rev. Nemoto, they prefer to not see their work as “suicide prevention”. They feel they should not tell people, “You musn’t die,” and put further shame on them. Rather, the way to ease their desire to die comes by being with them and accepting their feelings “just as they are”—in the same way the Pure Land practitioner feels accepted by Amida Buddha despite being filled with “afflictions” (klesha 煩悩 bonno), “just as they are.”

Out of this unusual congruence in view—for the academic scholar could see no greater separation in view than the “self-power” of Zen vs. the “other power” of Pure Land—a collaboration has been made by these two major denominations in the Kyoto landscape. In the afternoon, the delegation was led on a lengthy walk into the inner precincts of the Myoshin-ji temple, the headquarters of Japan’s largest Rinzai Zen lineage. In this haven, a place where the average citizen or tourist cannot enter, Sotto holds the Oden-no-Kai gathering for those feeling overwhelmed by life. Oden is a popular traditional Japanese food eaten in the cold weather of stewed vegetables, tofu, egg, and fish cakes. The nuance of the name is as a comfortable place where people can relax and warm their bodies and hearts by gathering together, just as oden becomes very tasty when various ingredients are gathered and cooked together. The gathering is held monthly on Wednesday, and lunch and snacks are prepared for everyone. It is subsidized by the Kyoto Prefectural Suicide Prevention Project.

Participants are encouraged to spend their time in their own way. Some confide their secret worries, others simply listen, and still others stay off to the side looking out on the beautiful Zen gardens of Myoshin-ji to rest their minds. The organizers believe that if there is a place where you can talk about any feelings you have without being denied, or a place where you can feel that you can be comfortable, it will be a place where you can feel safe. Rev. Kodo Kosaka, abbot of the Chokei-in sub-temple at Myoshin-ji where the event is held, explains: “We don’t have a specific way of counseling things one way or another. Eventually, we will approach them and ask, “Shall we discuss things together?’” One of the counselors in training explains that, “I want these people to come here and spend time with the staff and others who are suffering from similar problems, listening to other people’s stories and talking about their own, so that they can gradually relax”. The essence of this approach follows the Buddha’s teaching of the Four Noble Truths, that is, within the context of a sangha that is safe and takes the vow of non-violent speech, sharing one’s suffering (dukkha), the 1st Noble Truth, can lead to individual and collective insights into its causes, the 2nd Noble Truth, thus leading into the development of wisdom and compassion as expressions of the 3rd and 4th Noble Truths. Creating a safe space with no agenda also allows a dis-regulated nervous system to re-regulate, leading to increased energy, resilience, and insight to resolve troubling issues. In this way, the practice of sangha in Buddhism is congruent with the cutting edge of modern psychotherapy that involves somatic regulation with psychological insight.

Conclusion: Coming Full Circle in Holistic Development (kaihotsu)

Since the International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC) began documenting and supporting the Buddhist suicide prevention movement in Japan in 2007, we have seen numerous important changes as documented in this article:

- The destigmatization of suicide: Contrary to the popular image of Japan overseas, suicide has been highly stigmatized in modern Japan as a sign of weakness, a taint on the family lineage, and an inability to contribute to the collective and patriotic work of building the nation. Contrary to core Buddhist teachings that a person’s life and karmic path cannot be essentialized in one act, Buddhist priests have perpetuated the view of suicide as a stigma (kega-re). The suicide prevention movement has done much to eradicate this attitude within Japanese Buddhism and to support a more compassionate attitude in wider society towards sharing psychological difficulties and seeking support.

- Training and cultivating priests as compassionate listeners and psycho-spiritual guides: The suicide prevention movement has in many ways been a direct response to the malaise of Funeral Buddhism that permeated Japanese society in the postwar era. These priests have shown a great desire and energy to be there for persons in need before death happens, as in the classical model of Buddhist monks throughout Asia. The development of training systems in groups like the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide has in fact predated the now wider movement of train Buddhist and interfaith chaplains since the 3/11 tsunami and nuclear disaster.

- Reinvigoration of the temple as a sanctuary and safe haven: This is another important aspect of the resurrection of Buddhism in response to Funeral Buddhism. Buddhist temples have served as sanctuaries in Japan for lepers, abused women, and other marginal persons throughout history. This epoch will identify the suicidal and psychologically troubled as a new group for providing sanctuary to the common people

- Establishing grassroots ecumenical networks: Funeral Buddhism first took form in the late medieval Tokugawa Era (1603-1868), when the state completely co-opted what had been the dynamic and sometimes revolutionary Buddhist landscape. In this period, Japanese Buddhist denominations became very inward looking, and sectarian identities strongly developed. In Japan’s collectivist culture, such clannishness continued on in the modern era. The advent of social media has actually helped Buddhists of different denominations and backgrounds connect over common concerns, such as suicide prevention. The Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide is one of the first ecumenical, pan-sectarian networks to develop in this current era. Coming up from the grassroots, it also marks one of the first important new streams of socially engaged Buddhism in 21st century Japan.

- Integration into civil society and public policy: Again as a response to the marginalization of Buddhism in the modern era with the “separation of church and state” as well as Funeral Buddhism, the suicide prevention movement as a socially engaged Buddhist one has made significant strides in bringing Buddhist priests back into civil society, as seen in the work of Rev. Fujio as a community “gatekeeper”. At a time of great need in which the social and business networks of the postwar economic boom as well as government systems of social welfare have been deteriorating, Buddhist priests and temples have become increasingly active in social welfare work. This work also includes support for children and single mother’s falling into poverty, end-of-life care for the huge number of elderly, environmental advocacy for the victims of Fukushima, and holistic, community development (kaihotsu) for a new 21st century Japanese society.

- Holistic views of social change and social development: In the work of Rev. Nemoto mentioned in this article, we have seen how a Buddhist approach that blends the mind and body as well as the material and spiritual can offer not only a deeper understanding of preventing suicide but a new set of values and ethics for a post-postwar Japan. We began this article reflecting on Japan’s war trauma through Prof. Takeshima’s work and have considered that Japan’s great economic boom of the 1970s-80s and then disastrous collapse into a suicidal society in the 1990s-2000s is perhaps a neurotic response to the trauma of the war and the continued presence of U.S. military bases all over the nation. As also noted, for Japan to truly move forward, more than bureaucratic policies to “prevent suicide” will be needed. The work of the suicide prevention priests has provided an important contribution to this work, especially in the final visit of the Korean delegation in Kyoto to the new Tera Energy company.

Rev. Ryogo Takemoto is one of the co-founders of Sotto and a close colleague of Rev. Noro, mentioned earlier in this article. In early 2018, a meeting of the priests from the suicide prevention movement who have been developing international linkages was held at the aforementioned Kodosan temple in Yokohama. Rev. Takemoto made a startling announcement that he was leaving his position at the Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Research Institute and together with three other Hongan-ji priests was entering into a completely new realm of engagement. This was the formation of a Buddhist-based electricity company called Tera Energy, (tera = Buddhist temple). Since 2010, Takemoto had been deeply immersed in what can be described as the “holding action” of suicide prevention. He recalls there were many instances in which he felt he could not continue on with it, especially because of the strains of funding a non-profit that relied on grants and subsidies. This became the genesis of Tera Energy, whose motto is, “With a rich mind/heart (心 kokoro), we can move towards a secure future.”

On the face of it, Tera Energy would like to help realize the goal of more than 70 percent renewable energy (feed-in-tariff supply included) for the total electricity supply of Japan instead of relying unnecessarily on nuclear power. In this way, they are not only encouraging other Buddhist temples and their members as well as surrounding communities to switch their electricity supply away from Japan’s old, established utility companies but are actually offering them an alternative. In canvassing to find customers, they have been exposing the corrupt pricing system of these giant utility companies. Instead of overcharging customers to make profits to feed the insatiable appetites of big business, Tera Energy is able to charge less and still put aside 3.5 percent of their profits to create what they call the Warm Heart Fund.

The original Japanese for this Warm Heart Fund is hotto shi-san, literally meaning “assets for feeling relieved”. Rev. Takemoto explains this meaning in more detail by referencing his suicide prevention work based in Pure Land Buddhist teachings that seek to create “warm connections” (atataka-na-tsunagari) that overcome the sense of “disconnection” (mu-en) prevalent in Japanese society. From this fund, they make donations once a year to nonprofit organizations, temples, or other groups that are working on social welfare or social justice issues, such as climate change or suicide prevention. For Takemoto, this is a more systematic way to work on suicide prevention and ultimately heal Japan’s Disconnected Society. He explains:

These days, we want to enable people to feel a warm connection with others and to create a world in which no one has to feel alienated or alone. Our ultimate goal is to develop community around the Buddhist temples that are found everywhere in Japan so that no one has to feel left out and everyone can feel connected. The temple was the center of such local community for many centuries in Japan in the past. We want to emphasize creating connections in a society in which desire is not the determining factor. Such a society is a place where we can be connected beyond differences in race and religion and where we can also have an economic system that is based on sustainability rather than desire. We are trying to make a mechanism based on Buddhist ethics that is not based on desire, taking what is not given, or conflict over resources but is rather based on a sense of mutual trust and sharing.

In this way, Rev. Takemoto has connected the suicide prevention movement—sometimes circumscribed within the confines of the work to save troubled individuals—to the much wider world of “Buddhist holistic development” known as kai-hotsu in Japanese. This term was coined by the eminent development economist Prof. Jun Nishikawa (1936–2018) of Waseda University in his studies of Buddhist holistic development that have developed in South and Southeast Asia since the end of WWII. As a clever pun, it serves as an alternative reading for the same Chinese character 開発 for mainstream economic development known as kai-hatsu, using a traditional Buddhist reading of the latter term. This important linkage to socially engaged Buddhism further connects to the work of Jodo Pure Land priest, Rev. Hidehito Okochi, who learned of Buddhist-based micro-credit banking and such holistic development from numerous visits to these areas. In fact, his work pre-dates the establishment of Tera Energy by two decades in which he has used the sales of localized solar energy to fund a wide variety of community development projects. As Rev. Takemoto began to develop his work, the two were introduced and have become part of the international Eco-temple Community Development Project hosted by the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB). INEB has also served as a facilitator for IBPC’s spread into South and Southeast Asia with programs on Buddhist psychotherapy, chaplaincy, and suicide prevention.

In conclusion, while much of the Japanese world, including Buddhists, still looks West for clues to the next wave of modernization, these priests have begun to look South. This shift is not only important in going beyond modernity and its inherent mind-body dualism. It also builds solidarity with other Asian societies in a collaborative and horizontal form of sharing, different from the military and economic imperialism that Japan has waged since the end of the 19th century. As such, a pathway unfolds for the healing of Japan’s war trauma and, perhaps, with it, the healing of the suicide pandemic, as highlighted by Prof. Takeshima. Finally, the articulation of a holistic development model based on the ecumenical value of dharma as “natural truth” rather than Buddhism provides a pathway beyond the destructive paradigm of modern and post-modern capitalism that has led so many into a state of “karmic disconnection” (無縁 mu-en) and psycho-spiritual illness (dukkha).

See a previous article on the work in South Korea: Suicide Prevention in South Korea: The 2nd Life Respect Day Celebration and Policy Seminar March 25, 2022

For a more in-depth read into the issues of suicide prevention, war trauma, and Buddhist holistic development, see our new publications on Socially Engaged Buddhism in Japan!