The Warmth of Connection: A Buddhist Path to the Realization of Healing

Bangkok, Thailand

March 12-15, 2019

The International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB)Sponsored by

Japan Network of Engaged Buddhists (JNEB)

Siam Network of Engaged Buddhists (SNEB)

International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC) @ Kodosan, Japan

The era of modern, industrial capitalism & communism based in the dualism of mind and body has increased our fundamental human anxiety to new levels. The latest post-industrial era of mass media is intensifying this condition and reaching a tipping point in the worldwide epidemic of mental illness. As a response, incredible innovations are occurring not only in biomedical solutions but more importantly in new forms of psychotherapy. Buddhism finds itself in the center of this movement as western based therapeutic systems seek to import its concepts and practices, specifically mindfulness meditation. At the same time, practicing Buddhists worldwide are themselves experimenting with adapting traditional teachings and practices to new contexts. As innovations continue to grow and new techniques emerge everyday, one can feel as overwhelmed by the methods for healing as by the causes of suffering. In our work for suicide prevention in Japan and through our increasing connections worldwide with the Buddhist based end-of-life care, psychotherapy, and chaplaincy movements, we have been deeply impressed and moved by what we also find to be the fundamental simplicity of healing through re-establishing connection, or as the Japanese would say en 縁 (pratyaya), “karmic connection”. All the techniques and training courses and years of study are essentially trying to lead us to the simple yet fundamental healing qualities of connection, kindness, warmth, and community—something that your neighborhood grandmother perhaps knows better than your famous Buddhist master.

With these emerging lessons in our mind-hearts, a group of 20-30 monks, nuns, serious lay practitioners, and specialists in a variety of fields gathered for an International Roundtable on Buddhist Psychology, Psycho-Spiritual Counseling, and Chaplaincy Training from March 12-15 at the headquarters office of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) in Bangkok, Thailand. This meeting was the first major follow-up to the 1st International Conference on Buddhism, Suicide Prevention, and Psycho-Spiritual Counseling held in Yokohama and Kyoto, Japan from November 6-10, 2017. That conference was the culmination of over a decade of activities by the International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC) of the Kodo Kyodan denomination in Yokohama to nurture a collaborative network of priests in Japan working on suicide prevention. That conference also included as co-sponsors the Jodo Shin Hongan-ji Denomination Research Institute, the Ryukoku University Research Center for Buddhist Cultures in Asia (BARC), the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide of Greater Tokyo, and the Soto Zen Denomination Research Center.

In an effort to deepen understandings of key issues and develop further collaborative initiatives, the core group of participants from the first conference along with a select number of new participants met in Bangkok for four days of more intimate and focused discussion on the following themes: 1) the interface between Buddhist thought and modern psychology; 2) modalities for training Buddhist chaplains in psycho-spiritual care; 3) cooperative strategies & team building for medical and spiritual caregivers; and a new theme 4) confronting substance abuse through Buddhist methods. Participants came from Japan, Thailand, the United States, Myanmar, and India.

Workshop for Monastics on the Meaning and Practice of Death

Before the main meeting began on the 13th, a special meeting & workshop for monastics on the meaning and practice of death was held as a single-day event on the 12th. Initially, this meeting was planned as an exchange between Japanese priests working on suicide prevention and Thai monks working in end-of-life care. However, it grew to include Tibetan and Myanmar monastics, who enriched the discussions with their own viewpoints and experiences.

The core participants from Japan represented the Jodo Shin Pure Land Hongan-ji Denomination, the largest traditional Buddhist denomination in Japan. In 2010, a small group of their priests created a public, non-profit group called the SOTTO Self-Death & Suicide Counseling Center to offer counseling for the suicidal and grief support for the bereaved as well as to educate society about the issues of suicide. As Pure Land Buddhists, their understanding of humans as deeply flawed and unable to access bodhicitta through their own efforts is quite unique. However, their approach in the end is quite congruent with other Buddhist and other clinical chaplaincy approaches of “sitting quietly at one’s side” (the literal meaning of sotto). Their particular emphasis is providing the sense of warmth that a Pure Land Buddhist feels when embraced by Amida/Amitabha Buddha. However, as a public non-profit, they never communicate Buddhist teachings to clients, and like clinical pastoral education in the United States, the religious teaching and training is focused on the cultivation of counselors themselves. At the end of their presentation, they offered a short demonstration of the type of role-play training they provide their staff, which is mostly but not exclusively ministers from their Pure Land denomination. Two other priests from the Tokyo area of Japan, one from the Soto Zen sect and the other from the Jodo Pure Land sect, also presented on the work of offering special memorial services for bereaved families of those who had committed suicide. Because of social taboos against suicide and the intense sudden trauma of suicide, most families are not able to use the funeral of their loved one as a time to heal. New Buddhist associations like the Association of Buddhist Priests Confronting Self-death and Suicide are using private memorial services at major temples to gather such families to share experiences. As Japanese priests have often been criticized for making easy money by doing nothing but performing funerals, this transformation of the Buddhist memorial service is an important innovation for not only the public good but the revival of Buddhism in Japan.

The core participants from Thailand represented the Kilanadhamma Group for end-of-life care, which began from the individual work of Pramaha Suthep Suttiyano. Kilanadhamma started as a volunteer group of monks to visit and support dying patients in hospitals. This work has now begun to include the care of professionals who also experience suffering in this difficult work environment. Kilanadhamma has also expanded their work to a grief care program called Bhavana Forum, which invites twenty or fewer bereaved persons for a three-day program to share feelings and solutions to their grief. Like the Japanese, they have found the need to properly train monks to do this work and so have developed a four part program of introductory seminar, skills training, field training, and reflective conclusion. The group now has 60 monks actively involved. A second Thai group represented was the Buddhika Network for Buddhism and Society founded by Pra Paisan Visalo, the leading socially engaged Buddhist monk in Thailand who attended the last day of the conference. They began 16 years ago creating small workshops on care for the dying with nurses and doctors, and have continued to promote forums to bring monks and medical professionals together to develop better mutual understanding and collaborations beneficial to patients. In 2017, they held the Happy Death Day festival at Bangkok’s large Queen Sirikit Conference Hall that featured a wide variety of events to educate the public about death and shift attitudes away from the abject fear and denial of death that most modern people have.

Although only one brief day together, the entire group was inspired to learn of the wide variety of innovative activities toward dealing with death in contemporary society by traditional Buddhist monastics. While further follow up will be conducted, the group’s imagination was stimulated to think of a longer and wider ranging such program among Buddhist monastics of all traditions.

Main Conference Day 1: Roundtable on Interfaces between Buddhist Thought and Modern Psychology

Throughout the work of the priests in Japan doing suicide prevention, there has been the tension or contrast between the modern, predominantly western style of professional psychiatrist and the traditional style of Buddhist priest-counselor or what could be called “spiritual friend” (kalyanamitra 善知識). As our discussions have widened since our first international conference in 2017 to include the concept and role of the professional chaplain, there has developed a strong interest to continuing dialogue on the now popular theme of Interfaces between Buddhist Thought and Modern Psychology.

In short, the various traditions of Buddhism and modern psychology hold a generally common viewpoint on the nature and cause of human suffering in the neurotic patterns of the mind (1st & 2nd Noble Truths). Where there is great divergence, however, is in the vision or goal of psychological well-being and the means for realizing it (3rd & 4th Noble Truths). For example, what is the vision of personal well-being in modern psychology: to maximize individual coping mechanisms and performance in the world; to attain a state of psychological balance and therefore well-being? While nirvana is the stated goal of all Buddhists, the path towards getting there and the goals to be achieved along the way can vary greatly among traditions; for example, the extinguishing of all defilements (kilesa 煩悩) and attainment of meditative peace in the Theravada; the transmutation of such defilements and the attainment of bodhisattvic virtues in the Mahayana; or even the total acceptance of the defilements and the attainment of salvific embrace by the Buddha in the Pure Land tradition. These differences are critical in ultimately evaluating how traditional Buddhist teachings and practices are adopted into the modern world and used in different paradigms. For example, mindfulness meditation has very different connotations when used for: 1) the maximization of personal performance, 2) the attainment of a calming bliss, or 3) the transmutation of neurotic psychological processes.

The group was very honored to be led into these issues with a special opening talk by Dr. Yongyud Wongpiromsarn, Chief Advisor of the Department of Mental Health in the Thai Ministry of Public Health and Former President of the Psychiatric Association of Thailand. Dr. Yonyud began by pointing out how Buddhist interfaces with modern psychology have been taking place since the very advent of modern psychology, such as Shoma Morita (1874-1938), a Japanese contemporary of Freud who influenced by Zen started using mindfulness in his work, as well as Yoshimoto Ishin (1918-83), a Japanese Pure Land Buddhist who developed Naikan Therapy at the same time that western behavioral therapy developed. Dr. Yonyud himself started working on developing more accessible styles of the vipassana meditation methods of Goenka into his work 20 years ago.

The group was very honored to be led into these issues with a special opening talk by Dr. Yongyud Wongpiromsarn, Chief Advisor of the Department of Mental Health in the Thai Ministry of Public Health and Former President of the Psychiatric Association of Thailand. Dr. Yonyud began by pointing out how Buddhist interfaces with modern psychology have been taking place since the very advent of modern psychology, such as Shoma Morita (1874-1938), a Japanese contemporary of Freud who influenced by Zen started using mindfulness in his work, as well as Yoshimoto Ishin (1918-83), a Japanese Pure Land Buddhist who developed Naikan Therapy at the same time that western behavioral therapy developed. Dr. Yonyud himself started working on developing more accessible styles of the vipassana meditation methods of Goenka into his work 20 years ago.

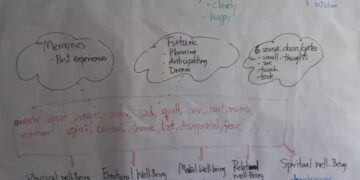

In explaining how using mindfulness in therapy differs from common western psychological therapy, he described what he calls the Basic Consciousness, which has the tendency to collect negativity and remember negative experiences, and the Higher Consciousness, which is resilient to negativity and the place where meditation has great effect. Mainstream Freudian psychoanalysis, the Cognitive and Behavioral therapeutic models which have now become predominant, and Humanistic psychotherapy which works on adjusting faith and beliefs basically all speak about correcting what is happening in Basic Consciousness. Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), pioneered by Jon Kabat-Zinn, and its offshoots like Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) and Mindfulness Based Therapy and Counseling (MBTC), all try to work on the Higher Consciousness and thereby transform and heal the problems of the Basic Consciousness. Because of this basic difference in approach, most of the mindfulness based therapies are trying to distance themselves from the more mainstream forms of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which use mindfulness as a tool for adjusting the Basic Consciousness. MBTC is a therapy that Dr. Yonyud is now developing and popularizing in Thailand.

After an incredibly stimulating presentation and discussion with Dr. Yonyud, one lingering thread left for further discussion was the problem of translating Buddhist terms for mental processes into English, which often has poor equivalents, and using them in secular psychological contexts. This problem also holds true for the adaptation of such terms within Buddhist cultures like Japan and Thailand where the new terms have lost touch with original meanings. At what point, do essential ideas and nuances get lost in translation? Furthermore, what happens to Buddhist concepts and practices when they are cherry picked out of their contexts, which are highly evolved with a rich series of checks and balances?

In the afternoon session, these themes were further discussed as participants spoke of each of their own particular traditions. Elaine Yuen of Naropa University in the U.S. noted that her teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche taught shamatha-vipassana meditation as an essential foundation and that the post meditation experience should be roughly 25% as specific mindfulness and 75% as general awareness. Rev. Shojun Okano, President of the Kodo Kyodan Buddhist Fellowship in Japan, also noted the essential elements of shamatha-vipassana (止観 shikan) in his Tendai (Ch. Tientai 天台) tradition. Neurotic thought patterns, or kilesa, should not be gotten rid of forcibly or denied but transformed through developing a balanced approach in which bodhicitta is cultivated. Rev. Akihiko Hisamatsu of the Soto Zen sect in Japan concurred that in Zen, the kilesa are seen as the raw material for enlightenment, like a stone that is polished into a gem through the practice of sitting meditation (zazen 座禅). Rev. Ichido Kikukawa of the Jodo Shin Pure Land sect in Japan offered a quite different perspective noting that as we are so vulnerable to our kilesa, we cannot develop bodhicitta through meditation but only gain it and salvation through the power of Amida/Amitabha Buddha. Rev. Shunsuke Kono of the Jodo Pure Land sect concurred and noted that while Pure Land teachings still value wisdom, it is in the process of relying on the “other power” (他力) of the Buddha that we are able to live a life of wisdom based in faith. Ani Losong Chotso, a Tibetan nun from the United States, noted the warmth and non-judgemental stance that the Pure Land priests offer in their counseling. Ani Pema, also a Tibetan nun from the United States, concurred that in her experience, people are healed as much by their inner resources as by connection, human kindness, and community. Ven. Nandiya, a Theravada monk from Shan State in Myanmar studying at the Walpola Rahula Institute in Sri Lanka, offered a similar perspective noting that the goal of the counselor is to become an ordinary person, not an elevated spiritual teacher, learning how to reduce harm and to function in the world. Finally, Pra Woot Sumetho of the Kilanadhamma group in Thailand, also noted that monks should not speak down but rather share, empathize, and support, empowering each person to face and solve their own problems through their own potentials.

In the afternoon session, these themes were further discussed as participants spoke of each of their own particular traditions. Elaine Yuen of Naropa University in the U.S. noted that her teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche taught shamatha-vipassana meditation as an essential foundation and that the post meditation experience should be roughly 25% as specific mindfulness and 75% as general awareness. Rev. Shojun Okano, President of the Kodo Kyodan Buddhist Fellowship in Japan, also noted the essential elements of shamatha-vipassana (止観 shikan) in his Tendai (Ch. Tientai 天台) tradition. Neurotic thought patterns, or kilesa, should not be gotten rid of forcibly or denied but transformed through developing a balanced approach in which bodhicitta is cultivated. Rev. Akihiko Hisamatsu of the Soto Zen sect in Japan concurred that in Zen, the kilesa are seen as the raw material for enlightenment, like a stone that is polished into a gem through the practice of sitting meditation (zazen 座禅). Rev. Ichido Kikukawa of the Jodo Shin Pure Land sect in Japan offered a quite different perspective noting that as we are so vulnerable to our kilesa, we cannot develop bodhicitta through meditation but only gain it and salvation through the power of Amida/Amitabha Buddha. Rev. Shunsuke Kono of the Jodo Pure Land sect concurred and noted that while Pure Land teachings still value wisdom, it is in the process of relying on the “other power” (他力) of the Buddha that we are able to live a life of wisdom based in faith. Ani Losong Chotso, a Tibetan nun from the United States, noted the warmth and non-judgemental stance that the Pure Land priests offer in their counseling. Ani Pema, also a Tibetan nun from the United States, concurred that in her experience, people are healed as much by their inner resources as by connection, human kindness, and community. Ven. Nandiya, a Theravada monk from Shan State in Myanmar studying at the Walpola Rahula Institute in Sri Lanka, offered a similar perspective noting that the goal of the counselor is to become an ordinary person, not an elevated spiritual teacher, learning how to reduce harm and to function in the world. Finally, Pra Woot Sumetho of the Kilanadhamma group in Thailand, also noted that monks should not speak down but rather share, empathize, and support, empowering each person to face and solve their own problems through their own potentials.

Main Conference Day 2: Roundtable on Training Buddhist Chaplains in Psycho-Spiritual Care and Cooperative Strategies & Team Building for Medical and Spiritual Caregivers

The conversations and themes of Day 1 naturally led into the themes of Day 2 of the conference, which focused on developing supportive relationships and structures for those coping with psychological suffering. For these sessions, we asked three participants from different regions with extensive experience in training counselors and working in the public sphere to lead the discussions.

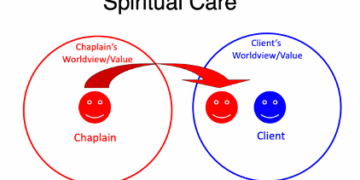

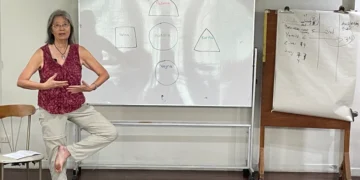

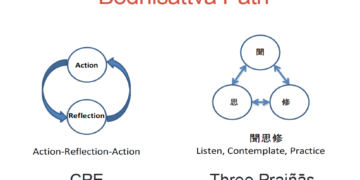

Elaine Yuen is an Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Chair of the Master of Divinity Program at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado where she trains and develops interfaith chaplains to work in public institutions such as hospitals. At Naropa, they have a dual training system for spiritual caregivers, which focuses on: 1) building the caregivers inner strength by accessing higher mind/consciousness, which is a mind of ambiguity or “not-knowing”. This is cultivated through courses in shamatha-vipassana meditation and other contemplative practices; 2) developing the skillful means (upaya 方便) to be able to guide others to make meaning for themselves. This is cultivated through a variety of courses on Indo-Tibetan Buddhist thought, such as Madhyamika and Atisha’s Lojong slogans. However, the training must go beyond acquiring techniques to the caregiver understanding how to be authentic to themselves and also learning boundaries so that caring for others does not become about healing something unresolved in themselves. After “not knowing”, “bearing witness” is a second essential modality to bring to the caring environment. [the third is compassionate action; these three were culled from Zen teachings by Roshi Bernie Glassman] Ultimately, being aware of inner and outer aspects is key in terms of not turning away from the suffering that is happening before oneself while trying to enliven both the outer environment and one’s inner being.

Mindfulness and meditation practice are obviously important for caregivers in dealing with the demands of “bearing witness” and “compassion fatigue”. However, Prof. Yuen and other Buddhists in the U.S. are now trying to integrate other Buddhist based contemplative strategies, such as “self-compassion”. Drawing on a variety of Buddhist teachings—especially the Four Divine Abodes (brahma-vihara) of loving-kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha)—American Buddhists in clinical and hospital environments are attempting to practice and transmit practices to develop warmth and understanding in oneself in times of professional suffering, failing, and feeling inadequate. Prof. Yuen explained that this involves practices to develop empathy and the ability to regulate one’s own arousal to situations so that one develops resilience rather than becoming overwhelmed. There is also the practice of perspective taking to develop congruence in goals and values between fellow clinicians and patients and their families. The practice of moral sensitivity is another important key in being able to recognize conflicts and obligations within the institution and to support caregiver decision-making. In this way, Prof. Yuen outlined the ways the holistic Buddhist approach of ethics (sila), meditation (samadhi), and causal insight (prajna) work together to support a caregiver in navigating the wide variety of issues that arise in working in healthcare organizations.

Pra Paisan Visalo is the founder of the Buddhika Network for Buddhism and Society developing networks of religious and medical professionals to integrate spiritual and physical care for the dying in Thailand. He noted that more work is needed to overcome the barriers in Thai Buddhist culture that wall off lay people from monks because of their sacred and celibate status. In this way, creating friendship with the patient in the beginning may be a problem for a monk, but ultimately it’s more about the monk’s attitude towards his own practice and identity. Monks must also learn that giving dharma teachings and preaching does not work with people in grieving and pain. The focus must first be dealing with all their anxiety, so it’s important to become friends first and to be present with them. Deep listening is the next step, but without purpose or agenda. The desire to heal or get the patient to move out of their suffering state is often something that obstructs the process of listening, creating a wall between the caregiver and the patient. However, it is often hard for monks to listen, because they may expect or feel they know the problem in advance. In this way, Pra Paisan’s approach to mindfulness and meditative training is to be aware of and accept everything that arises. This type of practice empowers someone to really be able to listen and develop compassion.

Pra Paisan also uses the practice of “not knowing” and learning the art of asking questions. The best questions are open ones like, “What happened to you?”; or “What is your feeling now?” These kinds of questions not only provide information to the caregiver but also help the patient understand themselves better. A third question can be, “What makes you suffer?” Patients may not even know how exactly how they feel now much less what is the cause of it. This question leads into the cause. A final question can be, “What can reduce your suffering?” The patient can often answer this themselves, with a certain amount of self-awareness or supporting atmosphere that helps them get free from disturbing emotions. This process of questioning is a skillful way to lead a patient through the entire process of the Four Noble Truths from suffering to causes to the path of cessation.

Rev. Ryogo Takemoto is a Representative of the SOTTO Self-Death & Suicide Counseling Center in Kyoto and a priest in the Jodo Shin Pure Land tradition. As with the observations of so many at the conference, they seek to recognize and affirm the patient’s experience rather than negate it by offering their own solutions or viewpoints. In this way, they prefer to not see their work as “suicide prevention”. They feel they should not tell people, “You musn’t die”, and put further shame on them. Rather, the way to ease their desire to die comes by being with them and accepting their feelings “just as they are”, in the same way the Pure Land practitioner feels accepted by Amida/Amitabha Buddha despite being filled with kilesa, “just as they are”. Rev. Takemoto again emphasized the importance of transmitting warmth through intimate communication.

In terms of training Buddhist priests in this work, they find that at the beginning most of them cannot interact properly. Some have a poor emotional response to the suffering person and their feelings. As their goal is to alleviate loneliness and provide warmth, the priest or caregiver needs to learn how to actually feel what it is like to be depressed. When Rev. Takemoto first practiced as a student, he responded to the person, “Oh that must have been difficult!”, and their response was, “How would you ever know!”. He explained that his comment showed that he was not feeling the person’s feeling but simply observing the situation from outside. The biggest question for them is: is the caregiver connected with the suffering person’s emotional center? It is a slight difference that makes all the difference. He remarked that if he had been really feeling the person’s pain, he could have said the same thing and the response from the person could have been, “Thanks for understanding. I don’t feel so alone now.” This seems simple in theory but very hard in practice, so they continually practice role-plays to develop their counselors. In terms of also developing resilience and avoiding compassion fatigue in this kind of practice, they emphasize working as a team, through monthly meetings amongst counselors to share their work and difficulties. Rev. Takemoto concluded that the living quality of warmth is key, and team building enables them to revive each other with warmth.

In the afternoon, these discussions expanded outward to the topic of strategies for Buddhists and religious professionals to develop partnerships with secular organizations and gain better public acceptance. Speaking from his own experience in Thailand, Pra Paisan commented that the indivisibility of social and spiritual transformation is the starting point. In the social activist world and in the medical world, the spiritual aspect is often missing, because the modern world view is still dominated by Cartesian Dualism. Because of this dualism, there are many cases in which doctors cannot find the physical cause of a sickness. In these instances, monks and religious professionals may play a role to show the links between spiritual well being and physical well being. Pra Paisan noted that Palliative Care is a field in which this can be more easily demonstrated, so it offers a good entry point for this work. Pra Win Mektripop of the Sekiyadhamma Network of Engaged Buddhist Monks, of which Pra Paisan is a founding member, noted how the Kilanadhamma group developed training methods that are now being used by the main monastic training university in Thailand, Mahachulalongkorn, as a good example of influencing mainstream institutions by first developing activities on the margins. A similar example of this was in 2018 when the official university of the Rinzai Zen Myoshinji sect, Hanazono University in Kyoto, hosted an entire program year of the Rinbutsuken Buddhist Chaplaincy training program.

In speaking of the barriers for Japanese Buddhists to work in mainstream society, Rev. Takemoto noted that as in many other countries, Japanese religious institutions had a tradition of medical and welfare care activities, but the government took over those roles in the modern era. Many Japanese priests actually work today as teachers or doctors, but they are not allowed to wear robes or have their identities as priests shown openly, so their work cannot be unified. However, the government has begun to downsize and outsource many social welfare services due to its financial problems, so this is an opportunity for religious groups and professionals to re-enter the public sphere. Rev. Akihiko Kikukawa also noted that in reflecting on Buddhism’s active support for fascism during the war years, Japanese priests lost confidence in themselves and withdrew from society. While the need to recognize mistakes from that period is essential, the response needs to be more pro-active by reviving the various medical and social welfare activities in which they used to be involved. Rev. Zenchi Uno of the Soto Zen Denomination Research Center in Tokyo explained that his Soto Zen sect has set up a basic program for some 6,000 priests to learn and promote deep listening practice. On the one hand, he noted, it is wonderful that their priests can be respected as counselors, and not just ritualists for funerals. However, he feels there is something mistaken in this approach, which loses the true sense of a priest as someone engaging people’s suffering as bodhisattva practice or as a “spiritual friend” (kalyanamitra 善知識). Bodhisttava practice is in fact deeper than being a counselor and can only be done from a religious or spiritual standpoint. In this way, he regards engaged Buddhism as a way to revive their true and original roles.

Interlude: Study Sessions on Substance Abuse & the Situation of Mental Care in Thailand

As part of our desire to always learn more from our host country, in this case Thailand, and to expand our frames of reference, the conference held an interlude day between the first and second main days of the roundtable.

In the afternoon, the group was able to take a study tour of the Somdet Chaopraya Institute of Psychiatry, located nearby. With Dr. Suttha Supanya as the host of the tour, we learned that it is Thailand’s oldest mental hospital and overall second oldest hospital, established in 1889 under the inspiration of King Rama V Chulalongkorn who had seen how the British were dealing with mental health problems on a visit to Singapore. With 500 beds (430 psychiatric, 70 neuropsychiatric), it acts as the major referral hospital in Bangkok. Dr. Suttha pointed out at the beginning that ideally psychological rehabilitation should occur at the community level, but Thailand has not yet developed such infrastructure so it still relies on this type of large mental hospital. There is, however, a form of community psychiatric care for patients who have been discharged. Especially for patients at risk of suicide, there is a hospital team that will provide home visits to check on patients. Just before our conference began there was a major article in the Bangkok Post about the sudden rise in suicide in past year in Thailand, especially among young people, which featured Dr. Yonyud’s analysis. Unlike this article, Dr. Suttha felt that unfortunately due to a poor understanding of suicide by the mass media and the spread of social media, news reports tend to be sensationalized, which seems to promote more repeat incidents. The hospital does have a Stress Management Clinic that uses Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and various relaxation methods. Another main reason for our visit to this facility was that a participant in the November 2017 conference, Dr. Polpat Losatiankij, is a resident psychiatrist there. He has recently conducted a study on mindfulness with chronic major depressive disorder and has begun an initial mindfulness based therapy program that runs regularly once a week.

In the afternoon, the group was able to take a study tour of the Somdet Chaopraya Institute of Psychiatry, located nearby. With Dr. Suttha Supanya as the host of the tour, we learned that it is Thailand’s oldest mental hospital and overall second oldest hospital, established in 1889 under the inspiration of King Rama V Chulalongkorn who had seen how the British were dealing with mental health problems on a visit to Singapore. With 500 beds (430 psychiatric, 70 neuropsychiatric), it acts as the major referral hospital in Bangkok. Dr. Suttha pointed out at the beginning that ideally psychological rehabilitation should occur at the community level, but Thailand has not yet developed such infrastructure so it still relies on this type of large mental hospital. There is, however, a form of community psychiatric care for patients who have been discharged. Especially for patients at risk of suicide, there is a hospital team that will provide home visits to check on patients. Just before our conference began there was a major article in the Bangkok Post about the sudden rise in suicide in past year in Thailand, especially among young people, which featured Dr. Yonyud’s analysis. Unlike this article, Dr. Suttha felt that unfortunately due to a poor understanding of suicide by the mass media and the spread of social media, news reports tend to be sensationalized, which seems to promote more repeat incidents. The hospital does have a Stress Management Clinic that uses Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and various relaxation methods. Another main reason for our visit to this facility was that a participant in the November 2017 conference, Dr. Polpat Losatiankij, is a resident psychiatrist there. He has recently conducted a study on mindfulness with chronic major depressive disorder and has begun an initial mindfulness based therapy program that runs regularly once a week.

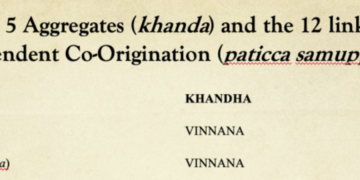

In the morning, we hosted three speakers who are using Buddhist methods to address the problems of substance abuse in their own countries. The first was Venerable Kuppiyawatte Bodhananda Thero, who offered his presentation in absentia due to visa complications. Ven. Bodhananda is the founder and the Director of the Mithuru Mithuro Movement, the first and the largest Buddhist Rehabilitation Centre in Sri Lanka, where they have successfully rehabilitated more than 5,000 young, male drug addicts since 1987. He has established and currently operates five rehabilitation centers around the country and a Leadership Development Center that can accommodate around 100 students, providing outbound training to students as well as professionals. Ven. Bhodhananda has creatively applied the Buddha’s classical teachings of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness called Satipattana to build a basic structure for his program. As Ven. Bhodananda explains, the Four Foundations roughly correspond to the key areas of a human being that should be addressed to bring upon long lasting change: the biological aspect, psychological aspect, social aspect, and spiritual aspect. In the first of these, the Contemplation of the Body (kayanupassana), they work on the rehabilitation of the resident by redeveloping their physical well being and basic physical discipline through meditation and a strict daily schedule that includes cooking and cleaning. The psychological aspect is addressed through the Contemplation of the Mind (cittānupassana), which focuses on peer and group counseling as well as the teaching of Buddhist psychology of the mind and meditation. For the social aspect, connected to Contemplation of Feeling (vedanānupassana), the rehabilitation of social skills and the ability to deal with difficult emotions is emphasized. One important activity in this area is an encounter program where residents are put in a controlled environment to safely express negative or difficult emotions they are having with another resident. There is also a program that focuses on family reconciliation. The final, spiritual aspect or Contemplation of Dharma (dhammanupassana) involves the development of the personality towards a religious or spiritually desired better personality. As a Buddhist organization, they focus on providing a good understanding of core Buddhist concepts, such as the Five Precepts, Dependent Origination, the Four Noble Truths, and the Noble Eightfold Path, which provide a practical grounding for integrating the other three areas of development. As residents continue to develop, they are given increasing responsibility within the community, becoming mentors to new residents and eventually gaining the chance to join the movement as staff. In this way, the program is not run as a “professional” organization with staff brought in from the outside, but rather as a “community” whose members are all in various stages of purification and practice.

In the morning, we hosted three speakers who are using Buddhist methods to address the problems of substance abuse in their own countries. The first was Venerable Kuppiyawatte Bodhananda Thero, who offered his presentation in absentia due to visa complications. Ven. Bodhananda is the founder and the Director of the Mithuru Mithuro Movement, the first and the largest Buddhist Rehabilitation Centre in Sri Lanka, where they have successfully rehabilitated more than 5,000 young, male drug addicts since 1987. He has established and currently operates five rehabilitation centers around the country and a Leadership Development Center that can accommodate around 100 students, providing outbound training to students as well as professionals. Ven. Bhodhananda has creatively applied the Buddha’s classical teachings of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness called Satipattana to build a basic structure for his program. As Ven. Bhodananda explains, the Four Foundations roughly correspond to the key areas of a human being that should be addressed to bring upon long lasting change: the biological aspect, psychological aspect, social aspect, and spiritual aspect. In the first of these, the Contemplation of the Body (kayanupassana), they work on the rehabilitation of the resident by redeveloping their physical well being and basic physical discipline through meditation and a strict daily schedule that includes cooking and cleaning. The psychological aspect is addressed through the Contemplation of the Mind (cittānupassana), which focuses on peer and group counseling as well as the teaching of Buddhist psychology of the mind and meditation. For the social aspect, connected to Contemplation of Feeling (vedanānupassana), the rehabilitation of social skills and the ability to deal with difficult emotions is emphasized. One important activity in this area is an encounter program where residents are put in a controlled environment to safely express negative or difficult emotions they are having with another resident. There is also a program that focuses on family reconciliation. The final, spiritual aspect or Contemplation of Dharma (dhammanupassana) involves the development of the personality towards a religious or spiritually desired better personality. As a Buddhist organization, they focus on providing a good understanding of core Buddhist concepts, such as the Five Precepts, Dependent Origination, the Four Noble Truths, and the Noble Eightfold Path, which provide a practical grounding for integrating the other three areas of development. As residents continue to develop, they are given increasing responsibility within the community, becoming mentors to new residents and eventually gaining the chance to join the movement as staff. In this way, the program is not run as a “professional” organization with staff brought in from the outside, but rather as a “community” whose members are all in various stages of purification and practice.

The second speaker was Mr. Rahul Bam, co-founder of Practical Life Skills Neuropsychiatric Wellness & Research Centre in Pune, India. Rahul noted that the defining factor of substance addiction is when harm is involved; in other words the loss of the first Buddhist precept. This is especially true of the untold harm to others. For a single addict, the lives of at least 20 people are directly affected. Their rehabilitation center called Santulan (“balance”) has a capacity 50 persons and is the only free drug rehabilitation center in India. In order secure certification by the Indian government, the program is limited to three months, the first month of which the addict is not allowed to leave the community. Much of their work is based in the research of Canadian physician Gabor Mate, who identified how the four basic brain circuits of edorphine, dopamine, adrenaline, and impulse control correspond to different drugs. The disease of addiction is one of disconnection due to a lack of nurturing and other issues in child development. As such, the brain develops deficiencies, and when a person takes a drug that meets that deficiency, their tendency to become addicted is strong. Rahul explained that talk therapy does not work with addicts. They may understand their issues but cannot control them. In turn, they use other therapies like art therapy in which the modality and goal are the same—a very Buddhistic understanding based in non-duality. Rahul then explained a very creative system they are using of applying the six Mahayana Buddhist perfections (paramitas 波羅蜜). At their second center, they are developing a system to find the correlation between the paramitas and observable therapeutic goals (TGs) employed by western psychology. For the paramita of patience (ksanti), there is development in impulse control and emotional regulation with stress management; for diligence (viriya), one works on consistency and planning & implementation; for meditation (samadhi), one develops sustained attention and analytical skills; for generosity (dana), one works on social & communication skills and empathy & understanding others’ perspectives; for discipline (sila), one works on self-care and instruction following; and for wisdom, (prajna) work is done in identification & understanding of the problem and consequential thinking. This second center has a strong emphasis in documentation and developing certified therapeutic tools so that their work can be more widely accepted in the professional world of rehabilitation and therapy.

The second speaker was Mr. Rahul Bam, co-founder of Practical Life Skills Neuropsychiatric Wellness & Research Centre in Pune, India. Rahul noted that the defining factor of substance addiction is when harm is involved; in other words the loss of the first Buddhist precept. This is especially true of the untold harm to others. For a single addict, the lives of at least 20 people are directly affected. Their rehabilitation center called Santulan (“balance”) has a capacity 50 persons and is the only free drug rehabilitation center in India. In order secure certification by the Indian government, the program is limited to three months, the first month of which the addict is not allowed to leave the community. Much of their work is based in the research of Canadian physician Gabor Mate, who identified how the four basic brain circuits of edorphine, dopamine, adrenaline, and impulse control correspond to different drugs. The disease of addiction is one of disconnection due to a lack of nurturing and other issues in child development. As such, the brain develops deficiencies, and when a person takes a drug that meets that deficiency, their tendency to become addicted is strong. Rahul explained that talk therapy does not work with addicts. They may understand their issues but cannot control them. In turn, they use other therapies like art therapy in which the modality and goal are the same—a very Buddhistic understanding based in non-duality. Rahul then explained a very creative system they are using of applying the six Mahayana Buddhist perfections (paramitas 波羅蜜). At their second center, they are developing a system to find the correlation between the paramitas and observable therapeutic goals (TGs) employed by western psychology. For the paramita of patience (ksanti), there is development in impulse control and emotional regulation with stress management; for diligence (viriya), one works on consistency and planning & implementation; for meditation (samadhi), one develops sustained attention and analytical skills; for generosity (dana), one works on social & communication skills and empathy & understanding others’ perspectives; for discipline (sila), one works on self-care and instruction following; and for wisdom, (prajna) work is done in identification & understanding of the problem and consequential thinking. This second center has a strong emphasis in documentation and developing certified therapeutic tools so that their work can be more widely accepted in the professional world of rehabilitation and therapy.

The final speaker was Pra Peter Suparo, a British monk representing the Wat Thamkrabok community, a temple situated in Saraburi, Thailand some two hours north of Bangkok. In 1959, it began a heroin and opium drug rehabilitation program under its first abbot Luang Por Chamrun Parnchand, a former policeman who was awarded the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1975 for the temple’s drug rehabilitation work. At present, there is a floating population of addicts in rehabilitation of 50-60 Thais and a handful of westerners that usually do not exceed 10. There are around 8 monks and 1 western nun who run the detox program along with another nun who is a qualified nurse. The larger temple hosts some 40 nuns and 160 monks. The temple practices the stricter, Thai forest tradition of Tudong from which much of the traditional knowledge of herbal medicine comes. From this tradition, the temple developed its unique detox program of meditation, a special herbal detox potion, and induced vomiting—which has drawn the attention of foreign visitors and has brought the temple international notoriety. The detox program has now developed a second branch for long-term alcoholics, especially older chronic users. Despite all the attention drawn to the special herbal potion and induced vomiting, Pra Suparo noted that many successfully rehabilitated addicts highlighted the program’s emphasis on vow (sacca 誠), which comes from one of the extended list of 10 Theravada paramitas, truthfulness or honesty. He explained that sacca is not just about being truthful but being authentic. After arrival at the temple, the addict first engages in a long group prayer and takes a vow “together with body, mind, and action”—the three doors of karma. As the specific teaching of karma in Buddhism is about the intention (cetanā 思) behind action, Pra Suparo noted that the many sacca vows the addict takes in the program are not about making promises to behave well but rather getting in touch with and honoring one’s own real intentions. Once one develops sacca at the level of mind as intention, then one tries to bring it into word. Can you make a verbal commitment that other people will hold you to? In this way, there is not a strict daily program imposed on the addicts in their time, and if they are unable to fulfill their own sacca, they are asked to leave. Pra Suparo pointed out that the deeper focus of the program and the temple is confronting the 1st Noble Truth of suffering (higher consciousness) rather than the more symptomatic condition of addiction (basic consciousness)—recalling the discussions from Dr. Yonyud’s presentation on the first day of the roundtable. A number of monks and part-time/full-time residents of the main temple living the much more formalized monastic life came from the detox program.

The final speaker was Pra Peter Suparo, a British monk representing the Wat Thamkrabok community, a temple situated in Saraburi, Thailand some two hours north of Bangkok. In 1959, it began a heroin and opium drug rehabilitation program under its first abbot Luang Por Chamrun Parnchand, a former policeman who was awarded the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1975 for the temple’s drug rehabilitation work. At present, there is a floating population of addicts in rehabilitation of 50-60 Thais and a handful of westerners that usually do not exceed 10. There are around 8 monks and 1 western nun who run the detox program along with another nun who is a qualified nurse. The larger temple hosts some 40 nuns and 160 monks. The temple practices the stricter, Thai forest tradition of Tudong from which much of the traditional knowledge of herbal medicine comes. From this tradition, the temple developed its unique detox program of meditation, a special herbal detox potion, and induced vomiting—which has drawn the attention of foreign visitors and has brought the temple international notoriety. The detox program has now developed a second branch for long-term alcoholics, especially older chronic users. Despite all the attention drawn to the special herbal potion and induced vomiting, Pra Suparo noted that many successfully rehabilitated addicts highlighted the program’s emphasis on vow (sacca 誠), which comes from one of the extended list of 10 Theravada paramitas, truthfulness or honesty. He explained that sacca is not just about being truthful but being authentic. After arrival at the temple, the addict first engages in a long group prayer and takes a vow “together with body, mind, and action”—the three doors of karma. As the specific teaching of karma in Buddhism is about the intention (cetanā 思) behind action, Pra Suparo noted that the many sacca vows the addict takes in the program are not about making promises to behave well but rather getting in touch with and honoring one’s own real intentions. Once one develops sacca at the level of mind as intention, then one tries to bring it into word. Can you make a verbal commitment that other people will hold you to? In this way, there is not a strict daily program imposed on the addicts in their time, and if they are unable to fulfill their own sacca, they are asked to leave. Pra Suparo pointed out that the deeper focus of the program and the temple is confronting the 1st Noble Truth of suffering (higher consciousness) rather than the more symptomatic condition of addiction (basic consciousness)—recalling the discussions from Dr. Yonyud’s presentation on the first day of the roundtable. A number of monks and part-time/full-time residents of the main temple living the much more formalized monastic life came from the detox program.

Conclusion: From Thought to Word to Deed

Taking a cue from Pra Suparo’s explanation of vow (sacca) and its manifestation in thought, word, and deed, we were able to reflect on the group’s development since the first conference in November 2017. That conference was very much focused on “thought” with a large number of presentations and exchange of information. This conference attempted to shift to a more conversational style of “word” to delve more deeply into the many issues that arose from the first conference. As we sat to discuss the merits of moving forward together, a consensus arose for more active forms of interaction in the style of “deed”. A number of sub-themes have emerged as essential for not only deeper exploration but also for sharing and training in methods which the group will move forward in developing, perhaps as smaller sub-conferences:

- Mindfulness: how to use mindfulness and meditation in authentically Buddhist ways to support those in suffering and their caregivers

- Ritual: how to use Buddhist rituals, especially those around death such as preparation for death and dealing with grief

- Compassion & other “emotional” tools: going beyond the emphasis on mindfulness and meditation, how to use the variety of “emotionally intelligent” Buddhist teachings and practices in therapeutic settings, such as the paramitas, the brahmaviharas, etc.

- Monastics workshop on death and ritual

- Religious trauma: clarifying and redefining misinterpreted Buddhist teachings that stigmatize mental illness and marginalized identity.