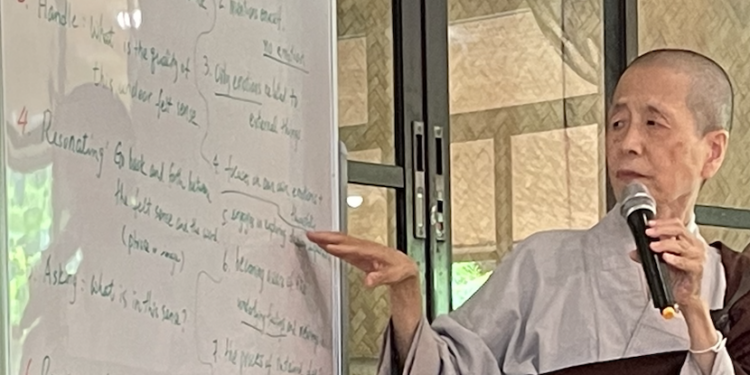

by Ven. Zinai with commentary Jonathan S. Watts

Ven. Zinai (Taiwan) was ordained in 1983 by the renowned bhiksuni Master Wuyin and Venerable Xinzi. Her works focuses on integrated Buddhist Abhidhamma studies, mindfulness meditation practice, creative education method based on Image Theory, and Satir’s Family Therapy Model. Jonathan S. Watts (U.S.A./Japan) studied and practiced at the forest monastery of Buddhadasa Bhikkhu in Thailand during the 1990s. Since 2006, he has helped to develop Japan’s first Buddhist chaplaincy training program, the Rinbutsuken Institute of Engaged Buddhism, where he teaches Buddhist social analysis and systems care.

March 15, 2024

I aim to explore how Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing methodology can be valuably applied to support Buddhist practitioners facing challenges in their meditative practice and daily lives.

A female Buddhist novice made significant progress during an intensive 20-day retreat focused on mindfulness of breathing. However, after her noticeable advancement, she unexpectedly experienced anxiety. With the guidance of a Focusing instructor, she went through the first four steps of the Focusing process and discovered that her fear of success was the root cause of her anxiety. Despite this challenge, she continued to progress steadily on her Buddhist meditation journey.

A retired female struggled with self-suppression, finding it is difficult for her to express her feelings and ideas, which caused her great frustration. Through Focusing therapy, she revisited a past experience of being frozen on stage during a singing performance. This process helped her understand how this traumatic event had suppressed her confidence and ability to express herself for over 20 years.

The integration of Western psychotherapeutic approaches with Buddhist meditation practice traditions presents both opportunities and considerations that require careful examination. While these traditions emerge from different cultural and philosophical frameworks, they share complementary elements that can enhance practitioner capacity to address suffering and promote wellbeing through a body-centered approach to inner experience.

For providing a comprehensive exploration on the value and methods of applying Gedlin’s Focusing in Buddhist community, I will remark on five themes as follows, 1. contrasting and connecting Buddhist practice and modern psychotherapy, 2. the significance of Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing in modern psychotherapy, 3. the Six Steps of Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing, 4. the works of the Focusing-Oriented guide, 5. consideration for integration and application.

Contrasting and Connecting Buddhist Practice and Modern Psychotherapy

1. Divergent Goals, Converging Paths

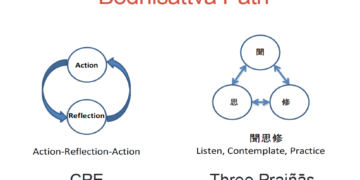

Buddhist practice and modern psychotherapy emerge from fundamentally different cultural and philosophical traditions with distinct primary aims. Buddhist practice focuses on enlightenment or nirvana through the transformation of consciousness, accessing inner wisdom, addressing existential concerns, and fostering overall well-being. In contrast, modern psychotherapy typically maintains a problem-solving orientation, addressing psychological and social issues while promoting psychological adjustment to internal and external challenges.

These differences extend to methodological approaches as well. Buddhist practice cultivates mindfulness and awareness through silent meditation, emphasizing embodied experience and the transformation of habitual patterns. Modern psychotherapy has traditionally relied more on intellectual understanding, verbal dialogue, and therapeutic knowledge provided by experts. However, these apparent contrasts conceal significant points of convergence.

2. Points of Intersection

Despite their different origins and aims, Buddhist practice and modern psychotherapy share important areas of convergence:

- Internalizing Attention: Both disciplines emphasize turning inward to observe mind-body phenomena. Gendlin’s Focusing guides this process through structured inquiry, while Buddhist practice cultivates sustained awareness through mindful meditation on body, feelings, thoughts or body-mind phenomena.

- Mindfulness and Emotional Regulation: Both acknowledge the significance of non-judgmental observation and skillful management of emotions. These complementary approaches offer different but compatible methods for developing a healthier relationship with emotional experience.

- Self-Compassion and Interpersonal Relationships: Both traditions recognize the importance of self-compassion and understanding in relationships, though they may articulate and develop these qualities through different practices and conceptual frameworks.

- Holistic Approach: Contemporary psychology has increasingly incorporated insights from Buddhist and other Asian traditions regarding the influence of the body and its energetic systems on the mind, as well as expanded states of consciousness. This represents a growing recognition of the wisdom contained in contemplative traditions.

3. Fundamental Differences in Purpose and Method

While these convergences create potential for meaningful dialogue and integration, the underlying differences in purpose remain significant. As Campbell Purton notes, “This, I suspect, is why focusing and meditation don’t really mix – they are aiming in different directions: focusing aims to resolve particular problems; Buddhism aims to free us generally from samsara”.

Buddhist meditation traditionally unfolds in two stages: first, samatha or tranquility meditation, which involves sustained attention to a single object to calm the flow of thoughts, followed by vipassanā or insight meditation, which turns attention to “experience as a whole”[1]. This progression differs from the Focusing approach, which systematically addresses specific concerns rather than seeking comprehensive insight into the nature of reality itself.

4. The Value of Focusing for Buddhist Practitioners

- Complementary Approaches to Suffering

Both Buddhism and focusing-oriented therapy share a fundamental concern with alleviating suffering, though they approach this aim through different frameworks and methods.[2] For Buddhist practitioners, Focusing can offer a complementary approach to addressing specific psychological obstacles that may arise during meditation practice or daily life. While Buddhist meditation aims at transformative insight into the nature of reality and the causes of suffering, Focusing provides tools for working skillfully with particular difficulties that may obstruct progress on the spiritual path.

- Addressing Specific Obstacles in Practice

Buddhist practitioners often encounter specific psychological challenges during intensive meditation retreats or in daily practice. These may include the emergence of unresolved trauma, difficult emotional patterns, or interpersonal conflicts that create barriers to deeper meditation. The structured methodology of Focusing can help practitioners relate to these difficulties in a way that honors both their Buddhist practice and their need for psychological healing.

From a Buddhist perspective, practices like Focusing belong more to the “compassion” aspect of Buddhism rather than the “insight” aspect. As Campbell Purton explains: “Meditation is designed to increase ‘insight’, which will lead to increased ‘compassion’, but meditation is not primarily concerned with sorting out personal difficulties in the way that psychotherapy is”.[3] This distinction helps position Focusing as a complementary practice rather than a substitute for traditional Buddhist meditation.

- Navigating Between Spiritual and Psychological Dimensions

For many contemporary Buddhist practitioners, particularly those in modern Buddhist practitioners’ contexts, finding a balanced approach that addresses both spiritual development and psychological health presents an ongoing challenge. Focusing can serve as a bridging practice that honors both dimensions without conflating them. It offers a methodology that is psychologically sophisticated while remaining compatible with Buddhist values of mindfulness, compassion, and non-attachment.

The Significance of Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing in Modern Psychotherapy

1. The Revolutionary Discovery of the “Felt Sense”

At the University of Chicago beginning in 1953, Eugene Gendlin conducted pioneering research spanning 15 years to determine what differentiated successful from unsuccessful psychotherapy outcomes. His groundbreaking conclusion challenged prevailing assumptions: therapy success depended not primarily on the therapist’s techniques, but on how patients internally processed their experiences during sessions. Specifically, Gendlin identified that successful patients instinctively accessed what he termed a “felt sense” – a subtle, bodily-felt awareness that contained critical information for resolving their psychological difficulties.[4]

This discovery represented a paradigm shift in understanding the therapeutic process. Gendlin found that “without exception, the successful patient intuitively focuses inside himself on a very subtle and vague internal bodily awareness—or ‘felt sense’—which contains information that, if attended to or focused on, holds the key to the resolution of the problems the patient is experiencing”.[5] This insight led Gendlin to develop a teachable methodology that could help individuals intentionally engage with this natural but often overlooked process.

2. Democratizing Psychological Healing

The development of Focusing democratized an aspect of psychological healing that had previously seemed mysterious or accessible only through lengthy formal therapy. Rather than positioning the therapist as the primary source of knowledge and insight, Focusing empowered individuals to access their own bodily wisdom through a structured process. Gendlin himself acknowledged the universality of this capacity, stating: “I did not invent Focusing. I simply made some steps which help people to find Focusing”.[6] This approach represents a significant shift from expert-driven therapy toward facilitating individuals’ inherent capacity for self-understanding and transformation.

3. A Process-Oriented Approach to Change

Focusing introduced a distinctive process-oriented approach to psychological change, contrasting with more content-focused therapies. Instead of primarily analyzing problems intellectually or seeking rational solutions, Focusing guides individuals to attend to the pre-conceptual, bodily-felt dimension of experience. This shift from intellectual understanding to embodied awareness has proven effective for addressing issues that resist purely cognitive approaches, offering a methodology that honors the body’s wisdom and the implicit dimensions of human experience.

The Six Steps of Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing[7]

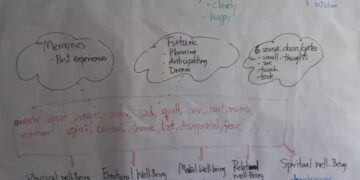

1. Clearing a Space

The Focusing process begins with creating a receptive internal environment. Gendlin describes this first step: “What I will ask you to do will be silent, just to yourself. Take a moment just to relax… All right—now, inside you, I would like you to pay attention inwardly, in your body, perhaps in your stomach or chest. Now see what comes there when you ask, ‘How is my life going? What is the main thing for me right now?’ Sense within your body. Let the answers come slowly from this sensing”.

For Buddhist practitioners, this step resembles aspects of preliminary meditation practices where one settles the mind and body before deeper practice. However, rather than aiming for a state of general calm, this step specifically involves identifying and acknowledging current concerns without becoming absorbed in them. The practitioner is instructed: “When some concern comes, do not go inside it. Stand back, say ‘Yes, that’s there. I can feel that, there.’ Let there be a little space between you and that”.

2. Felt Sense

In the second step, the practitioner selects one personal issue to work with, but maintains a particular quality of attention: “Do not go inside it. Stand back from it. Of course, there are many parts to that one thing you are thinking about—too many to think of each one alone. But you can feel all of these things together. Pay attention there where you usually feel things, and in there you can get a sense of what all of the problem feels like. Let yourself feel the unclear sense of all of that”.

This approach differs significantly from typical problem-solving or analytical thinking. Rather than breaking down the issue into components, the practitioner is invited to sense the whole of the issue as it manifests in bodily feeling. For Buddhist practitioners, this represents a shift from general mindfulness to a focused attention on how a specific concern manifests as a felt bodily experience.

3. Handle

The third step involves finding a word, phrase, or image that captures the quality of the felt sense: “What is the quality of this unclear felt sense? Let a word, a phrase, or an image come up from the felt sense itself. It might be a quality-word, like tight, sticky, scary, stuck, heavy, jumpy or a phrase, or an image. Stay with the quality of the felt sense until something fits it just right”.

This process of symbolic representation shares some similarities with certain Buddhist practices of labeling experience, but with a more exploratory and creative dimension. The emphasis is on finding an expression that resonates authentically with the bodily experience rather than applying predetermined categories.

4. Resonating

The fourth step involves checking the relationship between the felt sense and its symbolic expression: “Go back and forth between the felt sense and the word (phrase, or image). Check how they resonate with each other. See if there is a little bodily signal that lets you know there is a fit. To do it, you have to have the felt sense there again, as well as the word. Let the felt sense change, if it does, and also the word or picture, until they feel just right in capturing the quality of the felt sense”.

This careful attention to resonance cultivates a refined quality of awareness that aligns well with Buddhist mindfulness practices, but applied specifically to the relationship between bodily experience and language or imagery.

5. Asking

In this step, the practitioner deepens the inquiry: “Now ask: What is it, about this whole problem, that makes this quality (which you have just named or pictured)? Make sure the quality is sensed again, freshly, vividly (not just remembered from before). When it is here again, tap it, touch it, be with it, asking, ‘What makes the whole problem so…?’ Or you ask, ‘What is in this sense?’.

The instructions emphasize staying with the freshly-felt bodily experience rather than intellectual analysis: “If you get a quick answer without a shift in the felt sense, just let that kind of answer go by. Return your attention to your body and freshly find the felt sense again. Then ask it again. Be with the felt sense until something comes along with a shift, a slight ‘give’ or release”.

6. Receiving

The final step involves a receptive, non-grasping attitude toward whatever insights or shifts emerge: “Receive whatever comes with a shift in a friendly way. Stay with it a while, even if it is only a slight release. Whatever comes, this is only one shift; there will be others. You will probably continue after a little while, but stay here for a few moments”.

This non-forcing, receptive attitude resonates deeply with Buddhist values of acceptance and non-attachment. It acknowledges that transformation is often a gradual process that unfolds in its own time, rather than something that can be forced through willpower or intellectual effort.

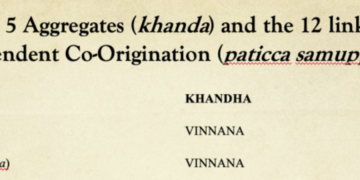

Go to A Buddhist Analysis and Commentary on the 6 Steps of Focusing Using the Buddha’s Teachings of the Five Aggregates (khanda) & Dependent Co-origination (paticca samuppada) (separate article by Jonathan S. Watts)

The Works of the Focusing-Oriented Guide

The works of a Focusing-Oriented Guide involve facilitating a process that helps individuals connect with their inner experiences and gain deeper self-awareness. These works include specific skills, techniques, and responsibilities that ensure a safe and effective Focusing experience. Key Works of a Focusing-Oriented Guide are as follows:

1. Holding a Safe and Accepting Space

Establishes a non-judgmental and supportive environment where the Focuser feels comfortable exploring their inner world. Ensures that the session remains gentle and non-intrusive, respecting the Focuser’s pace.

2. Guiding the Focuser into the Felt Sense

Helps the Focuser pause and pay attention to bodily sensations and emotions. Uses simple prompts like:

- “Can you notice how that feels in your body?”

- “Would it be okay to stay with that feeling for a moment?”

3. Reflecting Without Interpreting

Mirrors back the Focuser’s words and feelings to enhance self-awareness.

Does not analyze, judge, or offer solutions but instead deepens the Focuser’s connection to their experience. Example: If the Focuser says, “There’s a tightness in my chest,” the guide might say, “There’s a tightness there… just noticing that.”

4. Helping the Focuser Stay with Their Experience

Encourages the Focuser to sit with unclear feelings rather than rush to conclusions. May gently suggest:

- “Can you sense what this tightness might be wanting to tell you?”

- “If you stay with it a little longer, does anything new emerge?”

5. Supporting the Felt Shift

Recognizes when a felt shift (a subtle but meaningful change in bodily sensation) happens. Helps the Focuser stay with the shift so they can fully integrate the new awareness. Encourages them to acknowledge the shift with prompts like:

- “Does that change in sensation feel like a relief or something new?”

- “Would you like to thank your body for showing you this?”

6. Maintaining Neutrality and Presence

- Avoids directing or leading the session; instead, follows the Focuser’s process.

- Practices deep listening and trusts the Focuser’s inner wisdom to reveal what is needed.

7. Closing the Session Gently

Helps the Focuser transition back to daily life by grounding them.

Might ask:

- “How would you like to bring this awareness into your day?”

- “Would you like to check in with this feeling again later?”

The Focusing-Oriented Guide’s work is to facilitate self-discovery rather than provide answers. Their role is to help individuals trust their inner experience, allowing meaningful insights and healing to arise naturally.[8]

Considerations for Integration and Application

1. Maintaining the Integrity of Both Traditions

An important consideration in applying Focusing for Buddhist practitioners is maintaining the integrity of both traditions while exploring their potential complementarity. As Campbell Purton notes, there are potential dangers in taking practices out of their original contexts: “What I have said may point in the direction of a larger theme – that of whether there are dangers in taking a practice (such as tranquility meditation) out of one tradition (Buddhism) and transplanting it into a quite different tradition (psychotherapy)”.[9]

Mindfulness-based therapies already represent such a cross-traditional borrowing, and while evidence supports their therapeutic value, there is a risk of reducing mindfulness to merely a technique for addressing psychological difficulties. This could obscure its deeper purpose within Buddhism as a practice for gaining “experiential insight into the emptiness and interconnectedness of things”.[10]

2. Focusing as Complement, Not Substitute

For Buddhist practitioners, Focusing can serve as a valuable complement to meditation practice rather than a replacement for it. As Campbell Purton suggests, “From a Buddhist point of view, then, practices such as focusing, or psychotherapy generally, are of great value, but they belong with the ‘compassion’ aspect of Buddhism rather than with the ‘insight’ aspect”.[11]

This perspective allows practitioners to incorporate Focusing as a supportive practice when needed without confusing its purpose with the broader aims of Buddhist meditation. The complementary relationship can be understood as addressing different dimensions of human experience – Focusing addresses specific psychological obstacles, while meditation cultivates broader insight into the nature of reality.

Conclusion

The application of Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing for Buddhist practitioners represents a promising integration of Western psychological methods with Eastern contemplative traditions. While maintaining distinct purposes and philosophical frameworks,[12] these approaches share important common ground in their attention to embodied experience and commitment to alleviating suffering.

The six steps of Focusing provide Buddhist practitioners with a structured methodology for addressing specific challenges that may arise in meditation practice or daily life. By learning to access and work with the felt sense, practitioners can develop greater facility with difficult emotional material and psychological patterns that might otherwise create obstacles on the spiritual path.

At the same time, it remains important to maintain clarity about the different aims of these practices: Focusing aims to resolve particular problems, while Buddhist meditation seeks a penetrative and comprehensive realization of the reality of phenomena.[13] By maintaining this distinction while exploring complementary applications, practitioners can benefit from both traditions without conflating or diminishing either.

Future research might explore specific applications of Focusing in Buddhist retreat settings, detailed case studies of practitioners who have successfully integrated these approaches, and refined methodologies that respect the integrity of both traditions while maximizing their complementary benefits. Such integration, approached with both rigor and openness, holds significant promise for supporting practitioners on the path of spiritual and psychological development.

Notes

[1] http://www.dwelling.me.uk/Focusing%20and%20Buddhist%20Meditation.htm

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Focusing_(psychotherapy)

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://focusing.org/sixsteps

[8] The International Focusing Institute (www.focusing.org)

[9] Ibid., 4.

[10] Ibid., 4.

[11] Ibid., 4.

[12] Elizabeth English points out: “Any distinct system will hold its own particular insights and jewels. Often, it’s good to experience those first on their own terms, and within their own frame of reference”, in her writing on”Explorations in Focusing and Buddhism: 1. How Focusing can help Buddhist practice”. https://www.focusing.org.uk/explorations-in-focusing-and-buddhism-1-how-focusing-can-help-buddhist-practice/

[13] Ibid., 4.