Presentation by Rev. Fuminobu (Eishin) Komura

Tendai Buddhist Priest, former Staff Chaplain at Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Personal Background: For 37 years, he was an engineer at one’s of Japanese largest industrial technology corporations, Hitachi. Like many modern Japanese, he did not learn anything about Buddhism as a young boy, but when he was a child, he would think of the “other world” when watching the sunset and death often frightened him. Later, reading the Japanese classic, The Tale of the Heike Clan from the 13th century introduced him to Buddhism. When he lost his mother in 1994, after the cremation he felt her body had diffused into the air and would hopefully be absorbed by other plants and soil. Her spirit, however, would remain in the minds of those that knew her and this led to a personal epiphany after reading the Avataṃsaka Sūtra 華厳経 and the teaching of “One is all, all is one.” This gave him a powerful emotional experience of the interconnected nature of all dharmas over time and space from the beginning of time. Reading Thich Nhat Hanh’s book on interbeing which draws on this teaching made him confident about this experience. Eventually, in his 50s already, he decided to study Buddhism as a chaplain-in-training at the Naropa University Master of Divinity course in Boulder, Colorado. In order to finish his training, he also took ordination in Japan in the ancient Tendai denomination on Mt. Hiei.

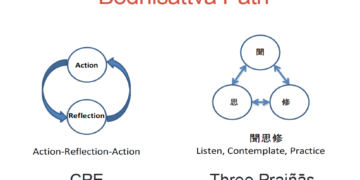

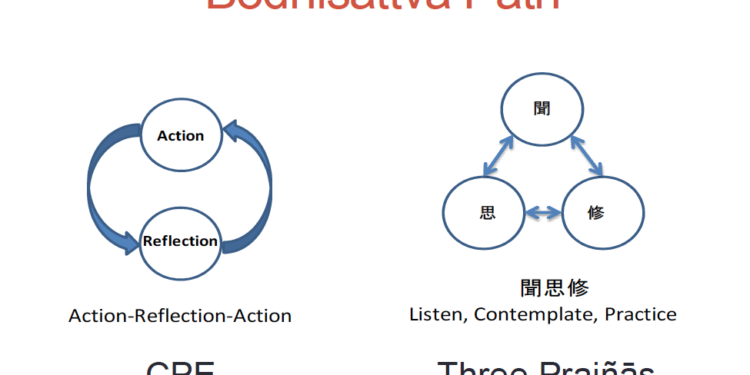

The Path of Buddhist Chaplaincy

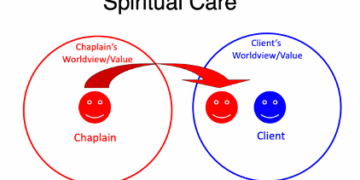

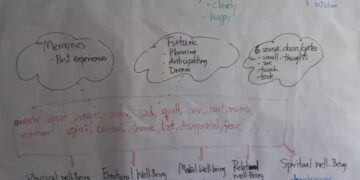

Rev. Komura’s basic philosophy of chaplaincy is less “doing” and more “being”, which means offering silent presence and bearing witness to the other’s suffering. The chaplain uses mindfulness—defined by Jon Kabat-Zinn as “paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and non judgmentally”—to cultivate the skill of “deep listening” (傾聴 keicho) and of non-judgemental attention to the self, the other or the environment.

In Rev. Komura’s experience in Philadelphia, he has often had to perform interfaith chaplaincy for people of other faiths, especially Christian. This has often involved issues not important or prominent in Buddhism, such as trying to answer the question: “If I have been a good person, why do I have to suffer so much?”. One participant noted that in Sweden he sometimes he meets people who use prayer to try to control outcomes, like, “If I pray in the right way, the cancer will go away.” or “If I connect in the right way I will be healed”. However, when this does not work, a cognitive and spiritual dissonance sets in. He tries to listen and join the person in the struggle, but he still feels it difficult to relate to. Another particiopants also spoke about her struggles to work with American Baptists who pray in a way that is very attached to outcome, such as, “Lord, please help heal our loved one with your blessings”. Furthermore, sometimes a family at the hospital would ask for things that the patient did not wish for. This is also an issue in Japan where the family collective is often prioritized over the individual patient’s will. While there has been a strong movement towards patient autonomy, she also has begun to use family systems thinking to consider the overall needs of the entire family.

A participant from Japan also spoke of this problem. In general in Japan, there is a strong emphasis on “this-worldly benefit” 現世利益 and the idea that those with true faith will be karmically rewarded in this very life. There is always this hidden motive, and when it doesn’t work, some see the reality that they have to change themselves. Others realize their prayers are selfish and resolve to release attachment. However, others just lose faith completely. In Buddhism we have “skillful means” (upaya 方便) to use if someone is in a desperate place, but in the end the person will need to face the facts.

In response, Rev. Komura feels it is not appropriate to tell a patient directly to release their clinging. In one experience with a patient looking for someone to answer her problem, he said to her, “I wish that you will be that person”; i.e. that you are the only person with the true answer. This was a very deep experience for both of them. Prof. Yuen then commented that this is the core challenge of chaplaincy. A nonverbal connection is often very useful in which the chaplain holds either metaphorically or actually the patients in their distress. A main question for the chaplain is: “How do we understand the liminal spaces?” and how can the chaplain help the patient utilize the paramita of patience to allow an answer to arrive. Rev. Komura concluded by saying that it is easy to feel uncomfortable in these situations and for chaplains to use a closing prayer as an “exit strategy” to avoid them. However, a closing prayer or ceremony, in fact, can make the experience of being with a chaplain sacred by restoring the patient’s connection with higher being.

Using this model of prayer he devised, Rev. Komura offers prayers for diverse groups of people:

- For Roman Catholics: the Lord’s prayer, Hail Mary, and Glory Be in English, Spanish, and Latin

- For Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhists, the chanting for Avalokiteśvara, “Oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ”

- For East Asian Pure Land Buddhists: Homage to Amitābha Buddha in Japanese, Chinese, and Vietnamese

- For Lotus Sutra and Nichiren Buddhists: Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō

- His personal diety is the Medicine Buddha, “Oṃ Bhaiṣajye Bhaiṣajye Bhaiṣajya Samudgate Svāhā”

- He also developed the Metta Sutta as a form of interfaith prayer: “May [one] be free from pains; be free from suffering; be filled with love and compassion; be happy; and be safe”.