by Jonathan S. Watts

see Ven. Zinai’s original article

Applying Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing for Buddhist Community: Bridging Therapeutic and Contemplative Traditions

Introduction:

-

- Is there a relationship between Gendlin’s “felt sense” & the Five Aggregates (khandha), especially vedana, which can be translated as “visceral feeling”? Can the Five Aggregates of form (rupa), visceral feeling (vedana), perception (sanya), cognitive thought (sankhara), and consciousness (vinyana) be reflected in the felt sense? Can the felt sense be used as a tool to observe and analyze the Five Aggregates?

-

- The purpose of the Five Aggregates and Focusing: Can the contemplation of the Five Aggregates help people achieve the purpose of Focusing, which is to gain more self-understanding and growth? Can Focusing help people achieve the purpose of the Five Aggregates, which is to break attachment to the self and liberate from suffering?

-

- The method of the Five Aggregates and Focusing: Can the contemplation of the Five Aggregates borrow the method of Focusing, such as using words or images to describe the phenomena of the Five Aggregates, especially “visceral feeling” (vedana) and perception” (sanya)? Can Focusing borrow the method of the Five Aggregates, such as using the perspective of impermanence, suffering, and non-self to view the felt sense?

The Six Steps of Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing with Buddhist Commentary

1. Clearing a Space: Much of this first step is comparable to how to begin with Buddhist meditation. As one step, it seems to contain 4 steps: 1) look inside, 2) ask, what is the main thing?, 3) develop a space between the answer and your awareness, which seems like practicing mindfulness (sati), and 4) keep exploring how you feel. From a Buddhist perspective, one problem with this approach is starting with language and cognitive questions like, “How is my life going? What is the main thing for me right now?” This seems like a much different question than, “How does something feel?” Shouldn’t the approach start with the very basic “felt sense” and then after a while ask these more complex questions about life and the main thing?

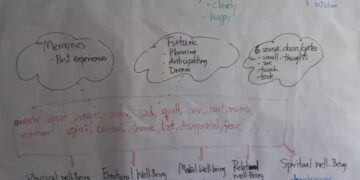

In the Buddhist contemplation of the Five Aggregates, one would normally start with the most “material” and move to the most “immaterial”: 1) rupa/form: establish your physical presence through posture and breathing, 2) vedana/visceral feeling: do a body scan & then choose a place that stands out & then determine the basic vedana of positive, negative, or neutral, 3) sanya/perception: label the feeling with single word adjectives, 4) sankhara/cognitive thought: one’s awareness tends to run off into cognitive thought, catch it, and come back to vedana and then engage in Gedlin’s questions about life and the main thing at this place, 5) vinyana/conscious awareness: notice how new thoughts from sankhara lead to new kinds of “contact” (phassa) and new states of vinyana, such as the shift from nauseousness to one of anger after a concocted thought arises. The arising of the Five Aggregates from coarse to fine also maps onto the process of Dependent Origination (paticca samuppada), where the conscious awareness (vinyana) of a sense object with a sense door in the body (rupa) gives rise to vedana and into more cognitive types of craving and attachment.

2. Felt Sense: Discovering the felt sense is similar to contemplating the Five Aggregates in reverse order, which is also included in Buddhist practice. As follows: notice a vinyana of anger, observe the details of your thoughts (sankhara), deconstruct the thoughts into impressions/perceptions (sanya), and then back into a fundamental feeling (vedana) in the body (rupa). There is also reverse paticca sampudda, where one starts from the experience of suffering (jaramarana & dukkha) and traces backwards to the basic factors and causes of its arising.

3. Handle: Focusing instructs us to ask, “What is the quality of this unclear felt sense? Let a word, a phrase, or an image come up from the felt sense itself.” Indeed, some people think more in images rather than a voice that speaks. Further, “It might be a quality-word, like tight, sticky, scary, stuck, heavy, jumpy or a phrase, or an image. Stay with the quality of the felt sense till something fits it just right.” This process is very similar to the stage of contemplating the aggregate of perception (sanya), which arises out of vedana or the felt sense.

4. Resonating: This is an interesting contemplation of watching the interdependent causality across the Five Aggregates. This act of resonating seems to develop a language or a communication between previously dissociated parts. From a modern standpoint, there is a basic dissociation between body and mind. Polyvagal theory, a more recent Western theory, would say a feeling that is too intense embeds itself deeply in the body as a dysregulated “felt sense”, making it very hard to connect to cognitive mind/higher mind, which could regulate it with wisdom and compassion. Buddhism would say early trauma has so conditioned the mind and created so many “ferments” or “outflows” (asava) that mindfulness cannot operate at the moment of sense contact (phassa) with wisdom or “clear knowing” (sampajanna). In this way, the causal chain of paticca samuppada rages uncontrolled and very rapidly results in attachment (upadana), arising of the ego-self (jati) and suffering (dukkha). Does Focusing help us work with these models of the Five Aggregates and Dependent Co-origination to develop clearer levels of understanding and regulation? When there is more connectivity is there less dissociation and greater wholeness and health?

5. Asking: We are told, “Be with the felt sense until something comes along with a shift, a slight ‘give’ or release.” From a Buddhist perspective, it seems like two things are going on here: 1) After experiencing the felt sense (vedana) and the handle (sanya), Gendlin warns of the arising of “a quick answer”, a kind of articulated or verbal response (sankhara); and 2) He then instructs us to “let that kind of answer go by” and continue to investigate with this question—What is in this sense?—“until something comes along with a shift, a slight ‘give’ or release”. This process seems somewhat like how one practices contemplation of paticca samuppada at the crucial moment of sense “contact” (phassa), which leads directly and usually very rapidly into “visceral feeling” (vedana). With sufficient mindfulness at “contact”, wisdom or “clear knowing” (sampajanna) can interrupt the reactive process of vedana—good, bad, or indifferent—and prevent the arising of attachment (upadana), ego-self birth (jati) and suffering (dukkha). This practice is well-known as an essential part of the Buddha’s final awakening:

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu—a highly regarded Thai master known for his creative and radical teaching of practical paticca samuppada—explains this term sampajanna. Sampajanna can be translated as “clear comprehension, ready wisdom, intelligence; clear seeing and intelligence applied to specific circumstances. Sampajanna draws upon wisdom accumulated through inquiry, practice, insight, and contemplation. Sampajanna often forms a compound with sati.” Further, “with a sufficiently developed practice, these four essential dhammas—mindfulness (sati), wisdom (sampajanna), clear comprehension (vipassana), and well-focused stability (samadhi)—will be ready to do their work at the moment of contact (phassa)”. [1]

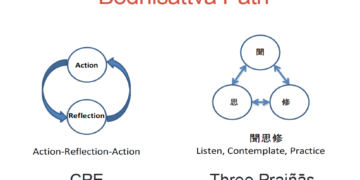

In terms of the Five Aggregates, one seeks to develop mindfulness (sati) at sense contact (phassa), and then observe how the sense contact concocts into vedana, sanya, and sankhara. This process parallels the one of paticca samuppada when after vedana, craving (tanha) and clinging (upadana) may arise. As with Focusing, we “just let that kind of answer go by”; that is, do not attach to the vedana or try to quickly let go of craving and clinging. Then, we continue the investigation “until something comes along with a shift, a slight ‘give’ or release”, which is akin to using mindfulness to create a space for the arising of wisdom (sampajanna), clear comprehension (vipassana), and well-focused stability (samadhi). In this way, there seems to be some connection between sampajanna and the “asking” stage of Focusing. With sampajanna, there is a natural dropping of ignorance and arising of intelligence. With Focusing, it seems one must engage in a more active intellectual process of asking the question “What is in this sense?”, but there is also a less directed aspect of allowing the feeling to speak. In Buddhism, this practice not only short-circuits the process of paticca samuppada, but by creating an open space, allows sampajanna to arise. This can begin a different causal process known as paticca nirodha that can begin with “wise reflection” (yoniso-manasikara), “moral conduct” (sila), or intelligent faith or confidence (saddha), culminating in nirvana, the final extinction of the ignorant, concocted self-ego.

In Ven. Zinai’s final section on how a Focusing-Oriented Guide can support, we learn about verbal cues and questions such as, “How would you like to bring this awareness into your day?” While Focusing is supposed to link you to the trauma in your body, it seems there is a still strong reliance on cognitive solutions. In Buddhism, we are taught to develop cognitive wisdom but the approach to awakening is very different in that solutions or liberations usually don’t come from the cognitive mind. There are experiences of “other power” and sudden awakenings coming from the withering away of neurotic networks and the opening to new forms of awareness. It seems Gendlin is getting at this with his guidance, “Be with the felt sense until something comes along with a shift, a slight “give” or release.” In Buddhism, there is a lot of “composting” with cognitive inputs from studying the teachings, but the process of awakening is quite alchemic involving energetic and physical dimensions, especially in Zen and in Vajrayana as well. From a Polyvagal theory standpoint, meditation creates the physical and energetic homeostasis we need for the higher mind to guide us through change.

6. Receiving: We are instructed to “receive whatever comes with a shift in a friendly way”. In one way, this goes against what the Buddhist meditator is instructed to do in maintaining non-judgmental awareness or mindfulness. Even to force oneself to be friendly may obscure forms of resistance that need to be uncovered. At the same time, there is the practice of “loving kindness” (metta) and compassion (karuna), which can be directed inward to enliven the mind and enable further investigation and practice. On numerous occasions, the Buddha spoke about the conditional dependence of wisdom and realization on the presence of non-sensual joy and happiness. Delight (pãmojja), joy (piti) and happiness (sukha) arise and lead in a causal sequence to concentration and realization. Without gladdening the mind when it needs to be gladdened, realization will not be possible.[2] Such a state would then enable what Gendlin next instructs, “Stay with it a while, even if it is only a slight release. Whatever comes, this is only one shift; there will be others. You will probably continue after a little while, but stay here for a few moments.”

Social Engagement:

An important and little known part of the Buddha’s teachings on Dependent Co-Origination is his instruction that the process can go beyond individual suffering and lead to communal strive, violence, and war. He taught that, “Now, craving (tanha) is dependent on visceral feeling (vedana); seeking is dependent on craving; acquisition on seeking, leading into ascertainment, desire and passion, attachment, possessiveness, stinginess, defensiveness. Various evil, unskillful phenomena then come into play, such as the taking up of sticks and knives, conflicts, quarrels, and disputes, accusations, divisive speech, and lies.” Maha-Nidana Sutta: The Great Causes Discourse, Digha Nikaya 15. Ven Zinai also gave a talk on this theme in 2024 at the International Network of Engaged Buddhists general conference on The Five Aggregates and Socially Engaged Spirituality

[1] Buddhadasa. Under the Bodhi Tree: Buddha’s Original Vision of Dependent Co-Arising. Ed. Santikaro. (Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications, 2017) pp. 180, 95.

[2] Analayo. Satipatthana: The Direct Path to Realization. (Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society 2003) p. 166.