Thai Participant #1

I feel like I’ve reconnected with a part of myself that I’ve long protected—my inner world, full of power and life. It’s a world I’ve kept hidden, one that’s difficult to express or share because society doesn’t normalize conversations about death. Death and related literature are often seen as taboo, too sacred, too frightening—or too difficult to accept as a fundamental part of life and dukkha. This inner world was something I saw reflected in my collage artwork.

There was a part of the process where I threw away twelve things that were important to me. As someone who has had many deep experiences, I’ve often moved forward in life by letting go of things that were dear to me—but I never had the chance to say a proper goodbye or truly grieve. I think I’ve often escaped rather than allowed myself to fully feel and accept. Many of these losses may seem small to others, but they held deep meaning for me—dogs, friends, relatives, even a house. Some of them aren’t even dead, like my ex-boyfriend or my mother, but they still represent loss—whether through breakups or rejection related to my sexuality or some of my gender or other identities.

This process gave me insight into my attachments, the worries and fears I carry about losing those I love. In a way, it showed me how my fear of loss is tied to a deeper refusal to accept death. It brought up anger and guilt about the nature of death and its relationship to the self and all sentient beings.

I’ve realized that I’m not deeply attached to material things, so letting go of them is easier. But losing people I love—especially when I don’t fully trust them or have lost faith in them—reveals the depth of my emotional attachment and my despair.

When I joined the workshop, I hoped to explore the nature of life and death through the lens of Buddhist truth-seeking. I felt happy and joyful to catch glimpses of this truth. I now see the need to balance both sides of life and death, much like the duality represented in the half-closed eyes of the Buddha statue I encountered during meditation.

Even though I didn’t understand the Japanese chanting, it felt familiar—similar to Balinese chanting, which I also don’t fully understand. The consistency of it brought me peace. The sudden shouts and loud bell ringing were startling, but they taught me something about mindfulness. Every time Ven. Nemeto made a loud noise, it startled me—but I began to understand that I don’t need to panic or feel shocked when sudden change arrives. That’s the wisdom I received.

In conclusion, I will continue to live my best life—fighting for justice and peace, while also offering those things to myself. I know that in my final moments, I may fear loneliness or lack of control, but I’ve already spent a lifetime in relationship with both life and death. I am committed to being present for my friends and loved ones in their life-and-death moments. This is how I now define my relationship with death: through practical, loving action.

Also it feels magical—and a privilege—to have learned all of this before the earthquake [in Myanmar and Bangkok on March 28]. It helps me accept natural disasters and situations beyond our control. It connects deeply with the meditation sessions, the Four Noble Truths, and the death festival event I previously attended with another group.

Phrai (Akekawat Pimsawan) INEB staff

Thai Participant #2

I attended three events with Rev. Nemoto: the SEM Annual Lecture on March 2, 2025, the first tabidachi workshop on March 4, 2025, and the two-day workshop at Wongsanit Ashram on March 10-11, 2025.

It was the second event – the tabidachi workshop – where I participated as a participant, that I gained some unexpected insights into myself. The reflections came from two activities, i.e. the artwork and the dying process with post-it notes.

For the artwork, I found myself unable to cut the magazine or search for meaning from outer sources. Instead, I drew something on my own even though I do not even have basic drawing skills. As a result, my picture board looked rather elementary, with faint colors and light traces, and lots of empty space. With only three symbols in the middle, it felt like a quiet echo of buddha dharma and emptiness. I was impressed with others’ work, especially those whose boards were so full. They have a strong sense of “self” and are full of stories to tell. Mine was a total opposite. While I felt that the board did reflect who I am, I was awkwardly aware of how different mine was from others.

The dying process with post-it notes stayed with me the longest, meaning I still thought about it even a month later. I found it perplexing that several people I talked to afterwards only remember three categories – important people, prized possessions, and to-do lists. Some thought there were 9 post-its. I remember that there were 12 post-its but don’t recall the fourth category [activities that you do regularly that are meaningful]. For myself, I thoroughly enjoyed this activity. To my surprise, someone important in my life showed up across all the categories. I hadn’t expected that level of interconnectedness. Another realization about self also surfaced. I realized later that many people had written “self” as the most important person and the last to let go of. I hadn’t thought about myself at all. This experience affirmed something I’ve noticed in other areas of my life especially in relations with others; that is, I don’t tend to put myself first. This is not necessarily healthy.

I feel that this exercise is valuable for everyone. It’s not just about letting go – it also serves as a reminder of what we must do to clear the obstacles to a peaceful death. I actually don’t remember what I wrote on all 12 post-its, and I am sure that if I were to do it again, my answers would be different. Nonetheless, one thing would still show up – the need to clean up. This exercise is a powerful reminder of my lingering fear of dying before I can deal with my “stuff”. I have way too many things to sort through – clothes, books, documents, printed photos, and other items I have accumulated over the years. The urgency of this task and the lack of energy to do it has been the most persistent stress of my life. To die and leave the burden for others to deal with my problem is an unconscionable thing to do.

Anchalee Kurutach (INEB staff)

Slovenian Participant

Earlier this March in Bangkok, I had the opportunity to join Tabidachi: A Death Workshop, a powerful experience hosted by the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB) and facilitated by Rev. Jotetsu Nemoto, a Rinzai Zen monk whose work has long accompanied those on the edge of despair in Japan.

The workshop invited us to step, gently and courageously, into a simulated death. What happens when we are given only a short time to live? What do we hold on to? And—more importantly—what are we willing to let go of?

Through guided meditation, creative expression, and carefully held rituals, we slowly peeled away the layers: people we love, roles we carry, dreams we chase, possessions we treasure. And at the heart of it all, each of us was left with one thing—our final thread.

It surprised me how similar our choices were. Some named “peace of mind.” Others, simply “myself.” For me, it was the connection to the source—what some might call the divine, or higher self. A quiet center that remains, even as everything else falls away.

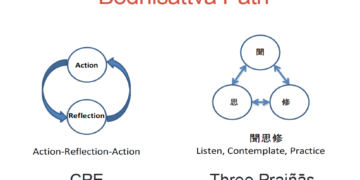

This work resonates deeply with what I’ve come to understand as the purpose of transformative education: creating spaces where people can touch deeper truths about who they are and how they wish to live. As a facilitator working in the field of engaged Buddhism, I’ve seen again and again how honest encounters with impermanence—whether through mindfulness, movement, or inner reflection—can crack us open in the most life-affirming ways.

I’ve had the honor of contributing to trainings like Awakening Leadership Training (ALT), Ecovillage Design Education (EDE), and Mindful Facilitation for Empowerment (Training of Trainers). In these diverse settings, one common thread runs through: the yearning to live more awake, more aligned.

The Tabidachi workshop was both an ending and a beginning. In “dying,” we glimpsed what it means to live with clarity and kindness. And as comrades in dukkha, we left with a renewed compass—one that points not away from death, but directly through it, toward what truly matters.

Petra Carmen

Swiss Participant

What does it mean to die? This is a question that I do not normally concern myself with. Of course, one thinks about death from time to time. After all, death is inevitable. But what does it really mean to die, not just the act of dying itself, but the journey towards death as well. It was an interesting experience to be faced with this question and to spend an afternoon immersing myself in the scenario of slowly traveling towards death. Participating in this workshop helped me to think more deeply about a process, which many of us will face eventually – if we do not die suddenly – and it further showed me that I might know myself better than I sometimes think.

During the workshop all the participants were handed out post-its and asked to write down the names of things, activities, goals, and people that are important to us. After that under the guidance of Rev. Nemoto we started the journey of someone who was diagnosed with an incurable disease. Our condition got worse and worse. One after the other we had to give up the things we held dear. Doing this allowed me for the first time to seriously consider, what it can mean to be diagnosed with a disease that will certainly lead to my death. Having to give up hobbies, having to give up dreams, starting to feel alienated from the people close to you, all while still trying to make the most of the rest of my life. It is a lonely process in which you end up losing more and more of what made you the person you were before.

Furthermore, this activity showed me very clearly what the most important things are in my life. I was surprised at how intuitively I knew what and who I wanted to have around me at the end of my life, when the disease had weakened me so much that I could only lie in a hospital bed. I saw the faces of the people who are the most important to me. This realization has had a very calming effect on me since then. Because I am someone who quickly doubts myself and I tend to overthink many things, especially my decisions. Realizing that deep down I know very clearly who and what is important to me has given me a new sense of confidence, which I took with me after the workshop.

Linus Dolfini (INEB staff)