A Zen Monk Brings Death Workshops &

Buddhist Suicide Prevention Counseling to Thailand

In life, not everything goes as you wish. There are times when you may feel frustrated, or when you may be overcome by the absurdity of things, or when you may be in the depths of sadness at the loss of someone you love, or when you may be seeking peace of mind.

If today was the last day of your life…what would you think about and what would you do? As you face death, you must let go of the things that are important to you one by one. What would be the thing left in your hands at that final moment?

When you become aware of death, it becomes easier to rediscover what is important to you in the course of your life up to that point. If you can feel what is important to you, it will become a source of strength to live more strongly, and you will also become kinder to others. Why not experience “departing” (tabidachi) together and make this precious moment of your life a fruitful one?

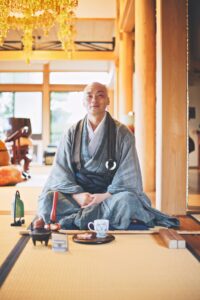

These are the opening words of invitation to the Departure (tabidachi), a death workshop run by Rev. Jotetsu Nemoto, the abbot of Daizen-ji temple in Gifu, Japan and a priest from the Rinzai Zen sect who has been working for two decades in suicide prevention in his home country. For two weeks, he brought his experiences, skills, and imagination to Thailand for a series of these workshops as well as a public talk and a two-day workshop on suicide prevention skills for monks and nuns from Thailand and Myanmar. These events were co-hosted by the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB), its partner affiliate in Japan called JNEB, and a new collaborative initiative called the Institute for Buddhist Counseling and Chaplaincy (IBCC). IBCC has emerged out of the efforts of JNEB and the International Buddhist Exchange Center (IBEC) at Kodosan temple to document and support suicide prevention work by Buddhists in Japan. IBCC has also emerged out of the efforts to train Buddhist chaplains in Japan and make chaplaincy programs that fit the specific Buddhist cultures across Asia.

While Nemoto’s work has become rather well known in Japan and also documented in foreign films like the documentary The Departure (2017), this was the first time for Nemoto to share his work outside of Japan. Work stress, relationship trauma, alienation, depression, and suicide have become a global problem beyond the confines of Japan’s Era of 30,000 suicides per year (1998-2011). Questions about the meaning of life and death have become especially acute in countries with high levels of economic growth and urbanization. Thailand, which has experienced rapid economic growth over the last three decades, is now one of these nations facing increasing levels of mental illness and suicide. While it shares a common Buddhist heritage with Japan, the two national traditions could be no farther apart with celibate, robe clad monks in Thailand and fully secularized, married priests in Japan. Still, their Buddhist roots, whether in the satipatthana (4 Foundations of Mindfulness) or zazen (seated meditation), have long traditions of confronting death directly as the most appropriate practice for gaining enlightenment.

Nemoto’s first event was held in Bangkok as a public talk at the 30th anniversary of the Spirit in Education Movement (SEM), a local affiliate of INEB in Thailand. SEM and INEB’s nonagenarian founder, Ajahn Sulak Sivaraksa (92) was in attendance and actively listened to Nemoto’s hour-long talk entitled, “The Enlightenment of the Suicidal: Dharma Healing & Experiences from Modern Japanese Society”. Like a true follower of the Zen way, Nemoto did not spend any time explaining psychological theories concerning suicide or providing commentaries on ancient texts. Rather, he told, in a very matter of fact way, stories of the many different kinds of people he has encountered in his twenty years of work: from highly educated persons who used Zen meditation to heal their minds to motor cycle aficionados supporting other suicidal comrades in on-line chat groups to two suicidal comrades who found life and love while trying to kill themselves on a Buddhist pilgrimage. The power of these stories felt much like the way Shakyamuni Buddha himself would teach through instructing others to investigate an issue directly rather than providing them with ready-made answers.

Nemoto’s first event was held in Bangkok as a public talk at the 30th anniversary of the Spirit in Education Movement (SEM), a local affiliate of INEB in Thailand. SEM and INEB’s nonagenarian founder, Ajahn Sulak Sivaraksa (92) was in attendance and actively listened to Nemoto’s hour-long talk entitled, “The Enlightenment of the Suicidal: Dharma Healing & Experiences from Modern Japanese Society”. Like a true follower of the Zen way, Nemoto did not spend any time explaining psychological theories concerning suicide or providing commentaries on ancient texts. Rather, he told, in a very matter of fact way, stories of the many different kinds of people he has encountered in his twenty years of work: from highly educated persons who used Zen meditation to heal their minds to motor cycle aficionados supporting other suicidal comrades in on-line chat groups to two suicidal comrades who found life and love while trying to kill themselves on a Buddhist pilgrimage. The power of these stories felt much like the way Shakyamuni Buddha himself would teach through instructing others to investigate an issue directly rather than providing them with ready-made answers.

Tabidachi Workshops

This talk was followed by two consecutive days of tabidachi workshops, one held for the staff of INEB, SEM, and affiliated groups and one for the general public. Rather than provide our own conclusions and impressions, we will provide testimonials of those who participated in these workshops as an attachment to this article. To provide a clearer sense of the workshop, it moved along as follows:

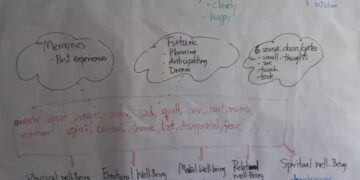

Participants were welcomed by Rev. Nemoto and provided basic instruction in Zen meditation. Unlike other forms of Buddhist meditation, Zen meditation, or zazen, involves very little instruction or teaching of methods. Simply, there is a great emphasis on maintaining a straight upright posture, then simply following the breath and becoming increasingly aware of the five senses. The practice is, therefore, amazingly direct and alarmingly uncluttered, with no techniques for the ego to hide behind or within. With the participants quiet and somewhat pensive awaiting instructions for death, Rev. Nemoto then unexpectedly had them engage in a one-hour Vision Board exercise. With a piece of white posterboard, a large pile of random magazines, glue, and colored pens, participants created a collage of impressions of their lives—again, as with the zazen—with little explanation of purpose or goal. Participants seemed to enter a liminal place in their life experience, becoming children again making art, either quietly in a corner or yapping together with others.

After posting their Vision Boards on the walls and taking a short break, participants were suddenly drawn back into the theme of the day, confronting death. Each participant was given 12 post-it slips, three each of four different colors, which corresponded to four themes: most important people in one’s life, most important possessions in one’s life, most important activities in one’s life, and most desired things to do before one dies. With these established and taking a meditative posture, Nemoto led participants through an imaginary scenario of themselves at the center in which they become diagnosed with a terminal illness and slowly lose their faculties to live independently. At each stage, Nemoto instructs them to throw away two or three of these posts as things “you can no longer be, have, or do.” The scenario ends with oneself on one’s deathbed surrounded by grieving loved ones while paralyzed and unable to speak, and then eventually fading away and “becoming the wind” (ka-ze-ni-natta)—and the last post is thrown away.

After posting their Vision Boards on the walls and taking a short break, participants were suddenly drawn back into the theme of the day, confronting death. Each participant was given 12 post-it slips, three each of four different colors, which corresponded to four themes: most important people in one’s life, most important possessions in one’s life, most important activities in one’s life, and most desired things to do before one dies. With these established and taking a meditative posture, Nemoto led participants through an imaginary scenario of themselves at the center in which they become diagnosed with a terminal illness and slowly lose their faculties to live independently. At each stage, Nemoto instructs them to throw away two or three of these posts as things “you can no longer be, have, or do.” The scenario ends with oneself on one’s deathbed surrounded by grieving loved ones while paralyzed and unable to speak, and then eventually fading away and “becoming the wind” (ka-ze-ni-natta)—and the last post is thrown away.

The final stage involves a “mock funeral” in which one has turned back from the tunnel of light of death and returns to consciousness in the hospital room. With only a random nurse left cleaning up the room to attend to you, the participant has ten minutes to express their final thoughts, feelings, and gratitude to others. In this role play, two participants act as partners with one serving as the nurse providing “presence” and deep listening while the dying patient has a white scarf covering their face during their time of reflection. At the end of the ten minutes, Rev. Nemoto rings his temple bell and begins chanting as during a funeral. After participants have experienced both roles, the workshop is brought to a conclusion with each participant sharing their Vision Board and offering their impressions of the death process.

Suicide Prevention Training for Monks and Nuns

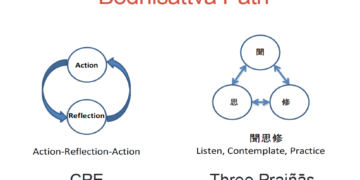

Nemoto’s Thai tour concluded at the Wongsanit Ashram, a forested retreat center outside of Bangkok that Sivaraksa established in 1990. As one of its first activities to bring various Buddhist chaplaincy and counseling skills to parts of Southeast and South Asia, IBCC gathered a group of 30 monks and nuns from Thailand and Myanmar for a workshop on suicide prevention and confronting death. While Nemoto’s methods, especially the tabidachi, and style of direct engagement as a secularized Japanese priest were quite foreign to the more conservative Theravada monastics, there was still a common base from which to share. As the core members of the IBCC have been discovering over the past few years of cross-cultural sharing, the Buddha’s seminal teaching of the satipatthana and the East Asian tradition of Chan/Zen share an emphasis on working first with the body and posture (kaya), which conditions and regulates the energetic body through “feeling” (vedana), which then allows one to confront the complexity of the cognitive mind (citta) and discover new insights into reality (dhamma). Within the satipatthana is also found the well-known contemplation of the stages of the dying corpse as oneself, which align with Zen’s emphasis on “the great matter of life and death” (生死事大 sho-ji ji-dai). This mix of shared foundations and widely different cultural styles made for a rich interaction.

As above, we will leave longer reflections on the workshop to a group of attached documents by the participants themselves and provide a simpler outline of the two-day event:

Both mornings began at 5:30 am with instruction in zazen in which the Theravada monastics were counseled to pay special attention to keeping a very upright and aligned posture, something not always emphasized in the tradition. On the first morning, Nemoto told an ancient Zen story from China to clarify the emphasis on Zen training in becoming mindful of the five senses as the foundation for all experience. There was also a chanting of the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra, an essential text in the Mahayana tradition that was available to Thai participants in a new local translation.

The first day of the workshop involved Nemoto “teaching”, again, through the use of case studies rather than psychological or spiritual analysis. His translator, this author, also presented on the wider suicide prevention in Japan, including the holding of special memorial services and group counseling for families and loved ones caught in the grief of those who had committed “suicide” or “self-death” (ji-shi). The latter term is now being used more commonly by Japanese Buddhist priests to remove the social stigma attached to “suicide” in Japan, which became more commonly referred to as “self-murder” (ji-satsu) under the influence of Westernization in the 1800s and 1900s (see more in Engaged Buddhism in Japan Vol. II). Nemoto then spoke deeply on the engagement with bereaved persons:

The first day of the workshop involved Nemoto “teaching”, again, through the use of case studies rather than psychological or spiritual analysis. His translator, this author, also presented on the wider suicide prevention in Japan, including the holding of special memorial services and group counseling for families and loved ones caught in the grief of those who had committed “suicide” or “self-death” (ji-shi). The latter term is now being used more commonly by Japanese Buddhist priests to remove the social stigma attached to “suicide” in Japan, which became more commonly referred to as “self-murder” (ji-satsu) under the influence of Westernization in the 1800s and 1900s (see more in Engaged Buddhism in Japan Vol. II). Nemoto then spoke deeply on the engagement with bereaved persons:

At memorial services for those lost to suicide, called tsuito-hoyo, I have often witnessed people crying and laughing simultaneously. The deeper the sorrow, the more poignant the warmth of memories becomes.

“Unforgettable, no matter how much time passes.”

“If only I could return to that day.”

With such thoughts in their hearts, attendees remember the deceased. Yet the gathering is not solely filled with grief.

“Do you remember that moment?”

“I can still picture their smiling face.”

When such words are exchanged, smiles emerge amidst tears. This is a time to affirm the life shared with those who have passed—a process of cleansing sorrow and taking new steps forward. Witnessing these moments reaffirms for me that human hearts are built on emotional complexity. It is this very complexity that upholds human dignity.

Human rights advocacy often emphasizes laws and systems. However, what truly matters is mutual respect and support between individuals. Moving forward despite conflicting emotions; cherishing memories while laughing through tears—these are uniquely human endeavors beyond AI’s reach. Therefore, I will continue creating spaces where people can live together amidst emotional complexity. No matter how much time passes or how far apart we may be—we will not forget. Transforming these feelings into “prayers,” we live on today.

That evening the group gathered to watch the very “uncut” documentary about Nemoto’s life and work called the Departure by Lana Wilson, which debuted in New York City in 2017 at the Tribecca Film Festival. “Uncut” means the film does not portray Nemoto as a heroic Zen master saving these lives of pathetic, suicidal people left and right. Rather, it shows what it really means to engage fully in the suffering of others and the way it can consume one’s own self, one’s own health, and the family and loved ones around them. In this way, despite certain shocking scenes for the Theravada monks—such as Nemoto drinking alcohol at a disco—the sincerity and depth of Nemoto’s bodhisattva vows to liberate numberless sentient beings struck a deep chord in them, as seen by their largely positive feedback the next morning.

The following morning participants worked in their own groups to not only reflect on practical considerations raised by the movie but also consider steps forward in developing forms of engagement with the suicidal and bereaved in their own localities. The afternoon and final session was devoted to the monastics experiencing the tabidachi workshop. In short, this featured a fascinating mix of certain monastics meeting the exercises with stoicism and the kind of guarded emotionality common to the Theravada tradition. Still, others became visibly moved while providing support to their dying partners, and many expressed deep emotional complexity in their final reflection and sharing of their Vision Boards.

Conclusion: First Step of Many

In a feedback and reflection session among the organizers held a month later, the impact of the tabidachi workshop was immediately noted with news that two Thai monks and a Myanmar nun had already started run their own versions of the workshop in their local regions. As noted above, there were certain cultural barriers in having Theravada monks and nuns hold hands during the dying process, but this was expressed as a more positive potential for growth in their training as compassionate listeners and also a unique aspect of this workshop. As the first time to hold these events outside of Japan, there were of course certain imperfections in the process, especially in the suicide prevention training workshop. Becoming a chaplain or counselor is one process, but being able to in turn train such persons is a different kind of challenge that established chaplains/counselors might not be especially skilled at. This point is evidenced in the United States where the path to train as a chaplain “supervisor” is far more arduous than the one of becoming a chaplain.

In a feedback and reflection session among the organizers held a month later, the impact of the tabidachi workshop was immediately noted with news that two Thai monks and a Myanmar nun had already started run their own versions of the workshop in their local regions. As noted above, there were certain cultural barriers in having Theravada monks and nuns hold hands during the dying process, but this was expressed as a more positive potential for growth in their training as compassionate listeners and also a unique aspect of this workshop. As the first time to hold these events outside of Japan, there were of course certain imperfections in the process, especially in the suicide prevention training workshop. Becoming a chaplain or counselor is one process, but being able to in turn train such persons is a different kind of challenge that established chaplains/counselors might not be especially skilled at. This point is evidenced in the United States where the path to train as a chaplain “supervisor” is far more arduous than the one of becoming a chaplain.

We hope to create these programs with Rev. Nemoto again in Thailand and other parts of Asia. In the meantime, seeds have been planted and are already taking root along with other initiatives by monks and nuns for supporting mental health in their local regions. Specifically, since the time of the workshop, a catastrophic earthquake hit northern Myanmar on March 28. The new local IBCC team for Thailand and Myanmar has already begun to design a program to teach monastics how to offer disaster trauma care for the victims with the support of a different group of Japanese priests who experienced and developed their work during the great tsunami of 2011. Stay tuned!

Report prepared by Jonathan S. Watts