September 26-27, 2023

At the Office of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists (INEB), Bangkok

The group welcomed 2023 and the lifting of most Covid restrictions around the world with work towards its first face-to-face international meeting since 2019. This work included welcoming new member-practitioners to our monthly zoom meetings as we attempted to build a participant list for the 3 activities we planned for Thailand in late September. These new participants have both widened the scope of our learning and work as well as deepening it in the areas already under investigation. While the group has re-affirmed its core intention to focus on 1) the problem of suicide (from which the project was initiated in 2017 in Japan), it has expanded its focus in two other major areas: 2) the intersection between modern, predominantly Western, psychotherapy & Buddhist teachings and practice, 3) the cultivation and training of Buddhist monastics and laypersons as counselors and chaplains. These three areas became the platform for creating three events in Thailand from September 24-October 1. This middle event, a two day intensive conference for advanced practitioners, provided the opportunity to delve even more deeply into the issues we have been studying together on Zoom since 2020.

Day 1 Morning, Session 1

Open Discussion on the Public Symposium:

How we are adapting modern psycho-therapeutic approaches into our sanghas

The 19 participants of this two-day intensive conference were asked to respond to the talks presented two days earlier at the public symposium on “Developing Buddhist Psychotherapy: Overcoming Contradictions in Psychotherapeutic & Spiritual Development”. Questions were especially directed at the keynote speaker Dr. Prawate Tantipiwatanaskul.

Ven. Yomin, a Malaysian Chinese monk living in Hong Kong, resonated strongly with two of the five points Dr. Prawate outlined for introducing Buddhist teachings into a psycho-therapeutic healing process. These were: 1) Avoid giving advice or directives in a teaching manner and focus on helping individuals learn from their own direct experiences within each of the four areas; and 2) Share information about useful principles at the right time, when individuals are ready to recognize and learn from it. In his own work, he has been trying to find a balance between teaching contemporary “mindfulness” practices and more traditional Buddhist approaches. He inquired as to whether these 5 points unfold sequentially? Dr. Prawate responded that there is quite a bit of flexibility in the way that Buddhism was taught by the Buddha. In psychotherapy, we use the term “attunement”, or to meet the people at the level of their experience. The approach needs to be tailored to the individual experience. We attune to the client, then check what they need and help them discover about themselves. Most of this learning comes with a dharmic flavor. In this way, a number of people he works with gravitate towards Buddhist teachings. Still, some severe cases cannot be treated with Buddhism alone. Yet in contemporary psychotherapy, he feels one-on-one counseling is actually not the best method, but needs to be more social. The social aspect is a healing process. We have to help clients own the issues of their life. If we address the problems of life, we often find they are spiritually based.

Jinji Willingham, a Buddhist psychotherapist and Buddhist chaplain in Austin, Texas (USA), feels that in the U.S. credentials play a very big role, and caregivers can over identify with their professional identity. There is a lack of connection in the U.S. between different types of caregivers as they are in competition with each other. There is a lot of professional aggression in words and thought. Many psychiatrists do not practice the art of sitting with clients. Talk therapy tends to come from the head, for example, in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). This is not relational. However, it is relationships that harm us, and it is in relationship that we are healed. In relational therapy, we share a third field of the meeting of two nervous systems. Such relationship can be healing. It is an acknowledgement that we are not separate. Itis not just “I”, it is “we”. This is the connection between the dharma and psychotherapy. Dr. Prawate responded that as a practitioner, he has tried to help clients connect to a deeper level. He has come to understand Buddhist theory much more deeply through relationship with his clients.

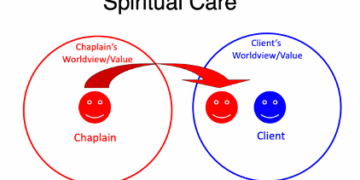

Cecilia Hadding, a medical doctor working in psychiatric wards in Sweden and a Zen practitioner, commented that to be a psychiatrist in Sweden, one is taught some psychotherapy as well. In this way, you can introduce and integrate secular mindfulness and meditation into your work but can never mention that you are a practicing Buddhist. For her, this creates a deep conflict as she sometimes feels that the client would benefit from a clearer explanation of the methods behind mindfulness. She also feels that self-compassion training needs to be included more in this work, and she finds that colleagues seek her out to discuss spiritual questions, because they know she is a practitioner. Dr. Prawate responded that he has the same problem. As a clinician, he tries not to impose his belief system on clients. When he started practicing psychiatry many years ago, he also started personal Buddhist practice. At first, he would use more evidence-based therapy models, but later on, the data came out on meditation and now there is evidence-based work on meditation that he can present to clients. As Thailand is largely a Buddhist culture, he can reference dharma easily without imposing Buddhism on them. However, he is always trying to strike a balance between his own beliefs and practices with the needs of the client. In this way, he feels a good process is that the therapist uses him/herself as a tool to attune to the client’s needs.In the West, it seems that in order for mindfulness to be accepted, all the other Buddhist aspects have been stripped away, but for many of us there is something more to learn from the original models of Buddhism.

Elaine Yuen, retired Chair of the Master of Divinity Program at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado (USA), explained that for her, Buddhist practice has helped her attune to people in a country that is 70% Christian. This involves interfaith practice where we are not allowed to even assume that a client wants any particular religion. Chaplaincy is about looking at how you can support people who are suffering. Then there is also a conversation about spirituality and religion. Religion is often seen as an institutional artifact, and its hierarchies can prevent people from going deeper into a spiritual understanding. The question then shifts to, “So what is your spirituality?” and one needs to do a diagnostic either cognitively or through emotional sensing. This approach is now common in chaplaincy training in the West. Brenda Phillips, a chartered psychologist and Buddhist chaplain at the University of Derby (UK), explained that clients are aware of her spiritual presence even if they cannot name it. She first trained a psychologist and then as a chaplain, and finds that there is a need to relieve spiritual distress not just psychological distress. So she asks herself, “To what extend am I meeting their spiritual needs?” She asked Ajahn Prawate whether he is that patients are picking up on his spiritual training, and how does this impact his model? Dr. Prawate responded that he has experience caring for those that are not Buddhist, but that the religious level is no barrier for people that approach him.

Day 1 Morning, Session 2

Open Discussion on Mindfulness vs. Satipatthana: What is the difference?

How do we build gateways from popular mindfulness practice

into the deeper system of Buddhist practice?

Building on the themes of the first session, the participants dove into this issue of how to connect the popular Buddhist-based mindfulness movement into the deeper systems of Buddhist practice, especially the traditional mindfulness and meditation system of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness or Satipatthana as taught by the Buddhism himself. In this context, the monastic participants were given the floor first to speak of their understanding of the Satipatthana.

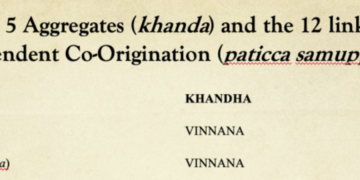

Pra Woot Sumedho, a Thai Theravada monk specializing in palliative and spiritual care in hospital settings, explained that satipatthana is the foundation of mindfulness with 4 approaches: body (kaya), emotion (vedana), mind (citta), and phenomena (dhamma). Mindfulness as sati operates through these four dimensions. Sati in this context is more about recognition. Sati is the awareness; patthana means “settlement” or the area we focus on. Satipatthana is like the context for the mindfulness. It is how you perceive things as they are and how you exist with that state. Phra Kru Sriwirunhakit Wasun, a Thai Theravada monk and co-founder of the Gilannadhamma monastic group for end-of-life care, explained thatwe can categorize mindfulness into two groups, daily life level and practice level. Sati in daily life is the basic causative level of refraining from doing bad things. On the deeper practice level, sati is about seeing things as they are, which comes from slowing down the mind process. It also involves looking inside to see observes dynamic changes and how all phenomena are impermanent. In this way, we lose attachment to sense objects, including mental ones, and the mind becomes calm. To go beyond attachment requires a deep level of practice. The result is going beyond suffering and attaining true happiness.

Ven. Zinai, a Taiwanese Mahayana nun from the Luminary Buddhist Nunnery founded by Master Wuyin, explained how Jon Kabat Zinn, the founder of the popular Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) method, has sought to teach more than just mindfulness. He tried to adapt and apply Buddhist teachings into the Western medical paradigm. MBSR teaches experientially the practices of satipatthana, such as body scan, and deeper teachings, such as “emptiness” (sunnata). In MBSR, as the dharma has been applied in response to the suffering of the world, it is liberated from the domination of the monastics. If we trace the mindfulness movement back, we find early origins in Myanmar and other parts of Southeast Asia as a response to the challenges of Western secularism and Christian missionary work by teaching lay people how to practice more deeply and intensely. Nowadays, some people speak of “McMindfulness” as it has been commercialized, so anything has come to be “mindfulness”. Even in Asia, such as her own country of Taiwan, she has been astounded to see a movement for mindfulness to disconnected from religion or Buddhism. The secularization of this practice has cut it off its roots. In response, some people are seeking to learn about satipatthana as there is more depth, even the deeper levels of vipassana are based on the Satipatthana Sutta.

Hendrik Tanuwidjaja, an MBSR teacher in Indonesia studying in the Vajrayana tradition, commented that in Indonesia the situation is quite different. Indonesians are quite sensitive to their feelings, and so they receive spiritual teachings wholeheartedly. Mindfulness has become popular because of the dukkha that arose during Covid. In Indonesia some psychologists know about MBSR but they don’t do the training. He is part of a group who are the first Buddhist meditators to also adopt and popularize MBSR. He thinks it is not about the two poles of Mindfulness vs Satipatthana, but another more extended line of Popular Mindfulness vs. Mindfulness based interventions vs. Satipatthana. As such, there doesn’t seem to be more interest in MBSR in Indonesia where popular mindfulness is stronger. A common question in Indonesia that he hears is, “After mindfulness, then what?” This reminds us of what the Buddha said in a sutta about Right View as well as Right Mindfulness making the Noble Eightfold Path complete. Many people practice mindfulness but have not captured or practiced Right View so they remain confused and dissatisfied.

Rev. Masazumi Okano, a Mahayana Tendai priest from Japan and head of the Kodo Kyodan denomination, responded to Ven. Zinai by noting that lay people were not traditionally introduced to meditation practice at the start. Instead, they would start practice with taking refuge in the Three Gems of Buddha, Dharma, Sangha. Then, they would learn the original ideas of karma and the workings of the afflictions (kilesa/klesha). The ultimate aim was to reach a better existence in the next life. In this pedagogy, you cannot start with meditation first but have to understand the dharma and how it relates to your own experience. On the other hand, in the West, they start with mindfulness and meditation with basically no dharma teachings on precepts, karma, or afflictions. However, if your lifestyle is in chaos, there is no way to practice meditation. First you must practice the precepts of not harming others and working to benefit them. Generosity (dana) is the other important aspect. The people that have followed such foundations are on the right track. In the meantime, the West has exported this focus on mindfulness back to Buddhist countries in Asia, and now many secularized people around the world dislike and distrust religion. In short, they want samadhi without sila or panna. In this way, we should not forget what the foundations are for Buddhist practice.

Rev. Gustav Ericsson, a Lutheran minister from Sweden who first training in Japanese Zen, responded that these are important questions for military chaplaincy as well.The language of Buddhism seems neutral when you first start studying the sutras, “to see things as they are”, but it is not really neutral. There are values and purposes within these practices and ideas. The problem is what do we mean when we say “to see things as they are”? For himself, when he encounters and enters a room of reality, he finds there is another room and then another. Do we mean “to see things as less conditioned”? Phra Kru Siddhisorrakij Pisut, a Thai Theravada monk recognized for his skills in Buddhist counselling, responded that when our mind is overcome by the emotions and the feelings related to an object, we cannot see the truth. Our biases influence our experience of the world. Phra Woot also responded that natural law has three characteristics: impermanence (annica), dissatisfaction (dukkha), and self-lessness (annata). Impermanence causes suffering, and this also applies to the self, because you cannot control everything.

Ven. Yomin explained that the two requirements of satipattana practice are to stay in the present moment and to know the reality of phenomena. Commercial mindfulness, on the other hand, just stays at the very surface level of being in the moment. In the book Satipatthana: The Direct Path to Realization by Bhikkhu Analayo, it is noted that there can be two definitions of pattana. There is the popular one of “foundation”, but there is another one from the term upatthana/upastana, meaning “to attend to, take care of, to hold”. In this term, the emphasis is more of an attitude of holding an object in the mind and experiencing its true reality. This gives us a broader and more inclusive view of mindfulness beyond those four bases. In this work, he also feels that traditional terms have to be more carefully translated into modern contexts, especially English. For example, instead of rendering dukkha as “suffering”, which seems to turn off people, he feels “dissatisfaction” is more relatable and touches the inner needs of people. The popular goal of “happiness”, therefore, becomes something deeper about how to reduce the Three Poisons of greed, anger, and delusion. Ani Pema, a Vajrayana nun from Australia doing counseling work in northern Thailand, responded that the Western view of “happiness” is to get and do as much as you can; “having, doing, being”; all external focused. She has noticed in this paradigm that no one is really happy. It seems to be a very distorted view of happiness.

Day 1 Afternoon

Group Workshops

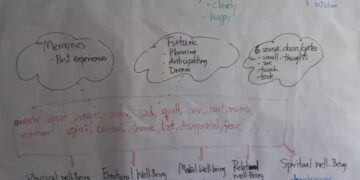

As practitioners, the participants were less interested in academic presentations and more on sharing a wide range of practices they use in their own clinical environments. In order to maximize the opportunity and to make the workshops more intimate, the afternoon sessions was broken into two time slots with 3 workshops happening at one time. While the space here and the format of the workshops does not allow an in-depth view of their contents and results, we offer these summaries of each one provided by their leaders.

#1: Walking Meditation (kinhin) in the Japanese Soto Zen tradition with Cecilia Hadding (Sweden)

In my tradition, regular sitting meditation or shikan-taza is the foundation of practice. It is hard and it takes both courage and strength to practice; but it also gives courage and strength. To lean in and to trust it is crucial. With regular meditation and “walking meditation” (kinhin), we get better in handling our own issues and developing the strength to meet others in need. The time or place is not always there to sit during a hectic workday nor for us or our students. Hence, I would like to contribute by teaching kinhin as it is done in my tradition of Japanese Zen in the Dogen Sangha led by Gudo Wafu Nishijima Roshi. Kinhin is much about finding balance in the body, a practice to refine balance in every moment, step, and every meeting with others. Kinhin builds a bridge from Zen practice to every aspect of my life, so that not only sitting meditation but working, playing and so on are also valued as a way of practicing Zen. It can be offered as a way to practice oneself and as a way to use in counselling by teach clients/family in secular and religious settings. Kinhin is a way to find balance in the body and to gather strength in oneself to be able to face other people with problems. It is also a tool to teach those who want to meditate but cannot to sit due to great psychological difficulties.

#2: The Science & Art of Happiness with Ven. Yomin (Malaysia/Hong Kong)

I have been co-teaching a course called “The Science & Art of Happiness – A Certificate Program on Positive Psychology & Evidence-Based Transformative Practice” co-offered by the Greater Good Science Centre, University of California, Berkeley, and the Tsz Shan Institute of Tsz Shan Monastery. While a professor from UC Berkeley explores happiness through a scientific lens, I provide teachings on the principles and techniques of meditation (focusing on mindfulness) together with the practice of self-compassion. Since the participants come from different ethnic, religious, and professional backgrounds, I have tried to plan the course in a way that caters to the needs of all. In sharing the practice of meditation, I try to use common words and the most simple method of bringing out the experience of mindfulness and self-compassion.

#3: Meditation for those with advanced cancer with Rev. Brenda Phillips (USA)

I have been leading a meditation support group for women with advanced cancer over the past four years. Each week I offer a guided meditation followed by council practice. I vary the meditations that I offer each week. Over time, I’ve found that we (myself and the patients) are drawn to “equanimity” (upekkha) practices. Several patients struggle to care for themselves while caring for others. In some cases, patients decide to stop treatment, but their families want them to keep “fighting” the cancer. I also have patients who are in their early 20’s who have been diagnosed with advanced cancer. Most of the people who attend are really struggling, and they are looking for ways to regulate their emotional experiences.

#4: Buddhist based suicide prevention with Jinji Willingham (USA)

This presentation on the Buddhist teaching of the Four Reminders (also known as “the four thoughts that turn of mind to the dharma”) began by discussing the spectrum of self-harmful behaviors to non-suicidal self injury (NSSI) and suicide ideation. It explored how the neurobiology of a distressed and traumatized nervous system can pose a threat to one’s well-being. Based on the Buddhist view of dependent arising or “interbeing,” we considered how we can help stabilize and co-regulate those who suffer from distress and trauma by establishing a secure relational dynamic and contemplation. With respect to suicide ideation, practicing with the Four Reminders (precious human birth, impermanence, samsara, and karma) has been effective in building connection, opening the heart to self-compassion, and re-discovering love and gratitude for this precious and impermanent human birth. Whereas most online versions of the Four Reminders end with samsara, the endless wheel of suffering, this approach ends with the message of choosing the positive over the negative, and therefore concludes with karma.

#5: Buddhist based counseling with Ven. Zinai (Taiwan)

I will briefly introduce the Open-Focus method of reducing stress-related symptoms and enhancing well-being. Then, we will practice in-and-out breathing meditation to centralize and stabilize ourselves as a helper or a chaplain. Next, I will introduce the six steps of Eugene Gendlin’s Focusing therapy, which provides the base for any counseling process as these six steps support a person to connect to one’s inner awareness. Finally, I will introduce how to use the Personal Iceberg Metaphor of the Satir Family Therapy model to develop a serial question to support going inside to clarify one’s inner strength and meaning.

Day 2 Morning & Afternoon (until 15:00)

Special Workshop on Maitri Space Awareness

with Elaine Yuen, PhD

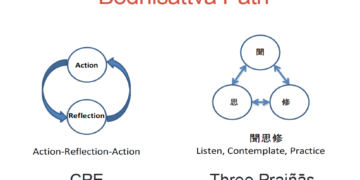

Maitri Space Awareness was developed by Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939-1987). Maitri or metta can be translated as “friendship”, and this practice invites us to befriend our experience through a contemplation of personal as well as environmental space. These inner and outer “spaces” are characterized through the principles of the Five Buddha Families found in Tibetan Buddhism. Each Buddha family expresses a different aspect of enlightened wisdom as well as confused, neurotic energy.

Maitri practice is based upon a trust in our basic human sanity, that we could directly experience these confused and sane energies of ourselves and others. For example, confused energies such as fear, anger, desire, and pride, can be related to directly, and experienced as awake qualities containing intelligence, vigor, and heart. These energetic qualities express as psychological states as well as elements that are found in our social and bult environments.

In Maitri practice, one learns how to recognize these qualities and work with them, in oneself as well as with others. Participants practice in specific postures in colored rooms for each Buddha family. Verbal direction is minimal, and thus invites thoughts and non-conceptual reactions to the practice experience(s). Time is then given for contemplation and reflection. Reactions and insights are often very personal, with individual insights of how one personally relates to specific situations. For instance, some may find different reactions to the Ratna family, which represents wealth and groundedness as well as a poverty mentality and FOMO (fear of missing out). Maitri Space Awareness develops an ability to recognize and “be with” different emotional and environmental states, and is a key part in the MA contemplative counseling program at Naropa University.

In this introductory workshop, the participants spent the day spending time and practicing with each Buddha Family. For each of the five families, we had a theoretical explanation of its elements by Prof. Yuen; followed by a period of direct practice involving specific bodily positions in colored and curated rooms as devised by Trungpa Rinpoche. After the direct practice, experience(s) were contemplated in silence through a period of “aimless wandering” and then harvested collectively with the entire group. For further readings in this work, see “Maitri Space Awareness in a Buddhist Therapeutic Community” in The Sanity We Are Born With by Chogyam Trungpa (Shambhala, 2005) and “Transforming Psychology” by Judith Lief in Recalling Chogyam Trungpa (Shambhala, 2005).

Day 2 Final Session

Future Planning for 2024 and Beyond

In the last session of the conference, the group spent time discussing a variety of short, medium, and long-term plans for this work. These will be presented in greater detail in 2024, but in short, they cover areas concerning:

- media & publicity: Besides the information and updates provided on our website, some members are looking into various ways of sharing the insights and practices of our group, perhaps in videos offered on Youtube.

- suicide prevention: various small projects on developing specific Buddhist based tools for supporting those with serious mental illness and suicidal ideation. There is also a plan for a Japanese-Korean Buddhist exchange on suicide prevention.

- youth education & support: Developing educational materials and support mechanisms especially targeted at teenagers and young adults who especially struggle to cope with this hyper post-modern world.

- Buddhist psychotherapy: ongoing projects on increasing the connectivity between deeper forms of Buddhist practice and contemporary psychotherapeutic methods, such as the discussion above on mindfulness vs. satipatthana.

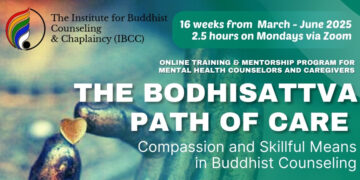

- Buddhist chaplain training: developing more programs in Southeast and South Asia, perhaps through small teams of trainers visiting and conducting workshops in various countries.

- Maitri Space Awareness: various members are committed to further developing this system as a form of authentic Buddhist psychotherapy.

Keep in touch and hope to see you out there in the real Metta-verse!